The AdS/CFT correspondence is a conjectured equivalence (duality) between two very different types of physical theories: a gravitational theory in a higher-dimensional Anti-de Sitter (AdS) spacetime, and a conformal field theory (CFT) living on the boundary of that AdS space.[5] In simple terms, it asserts that physics inside a bulk AdS universe (with gravity) is exactly equivalent to the physics of a lower-dimensional quantum field theory without gravity defined on the boundary of that universe. This duality is often called a gauge/gravity duality or holographic duality, because a gauge theory (like a Yang-Mills CFT) on the boundary is dual to a gravity theory in the bulk.[3] The correspondence provides a dictionary between the two: every object or phenomenon in the AdS bulk (e.g. a particle or a black hole) corresponds to some entity in the boundary CFT, and vice versa. Despite the theories living in different numbers of dimensions and looking very different, they contain the same information and physical content - they are in fact identical in all their predictions when the duality holds.

AdS/CFT is a concrete realization of the holographic principle in physics. The holographic principle, first suggested by Gerard 't Hooft and Leonard Susskind in the 1990s, posits that all the information contained in a volume of space can be described by data on the boundary of that space.[6] An analogy is a ordinary optical hologram: a 2D film can encode a fully three-dimensional image. Similarly, in AdS/CFT the CFT on the two-dimensional boundary encodes everything about the three-dimensional (or higher-dimensional) AdS bulk. In fact, AdS/CFT is often described as a “holographic duality” because the relationship between the bulk and boundary is like that of a 3D object and its 2D hologram. The boundary theory is like a hologram that captures information about the higher-dimensional bulk gravity theory. In short, gravity in AdS spacetime is holographically encoded by a field theory on the boundary. This idea revolutionizes how we think about space and gravity: the correspondence suggests that the familiar concept of a spatial volume with gravity can emerge from a lower-dimensional, gravity-free quantum system. The AdS/CFT duality gave a precise example of holography at work, showing that the number of degrees of freedom in a region of space truly scales with the area of its boundary and not its volume (exactly as 't Hooft and Susskind had anticipated).

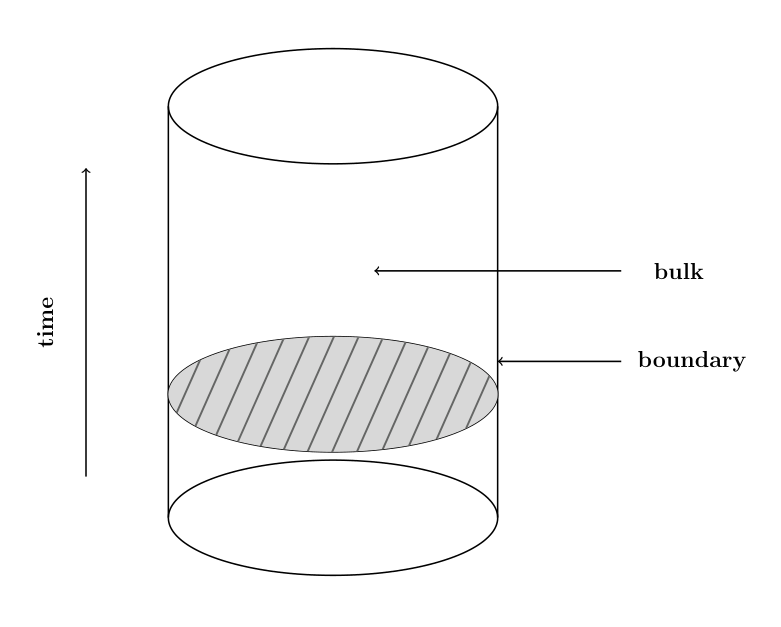

A useful way to visualize AdS spacetime is as a cylindrical shape, where the upward direction represents the progression of time, and each horizontal cross-section corresponds to a spatial snapshot at a specific moment. In this representation, the associated conformal field theory (CFT) can be thought of as residing on the boundary of the cylinder. Notably, this boundary has one dimension less than the interior, often referred to as the “bulk.”[7]

Historical and Theoretical Context

The AdS/CFT correspondence was first proposed by Argentine physicist Juan Maldacena in 1997 (published early 1998) in a groundbreaking paper that has since become one of the most influential in theoretical physics.[4] Maldacena’s work was inspired by earlier ideas of holography and by results in string theory. He considered a specific scenario in string theory and conjectured a duality between a 5-dimensional AdS spacetime and a 4-dimensional CFT on its boundary. In particular, he showed that under certain conditions (including a high degree of supersymmetry), Type IIB string theory on an AdS5 × S5 background is dual to a 4D CFT (known as N=4 supersymmetric Yang-Mills theory) living on that AdS boundary.[3] This was the first concrete example of a “holographic universe.” Maldacena’s proposal had an immediate and enormous impact: it provided a tangible framework to unite quantum field theory and quantum gravity. The discovery was so remarkable that it kicked off an explosion of research; indeed, Maldacena’s paper is among the most highly cited physics papers ever. By the 2010s, many physicists regarded AdS/CFT as one of the most exciting discoveries in modern theoretical physics. It not only advanced string theory but also offered new tools to tackle problems in other areas of physics.

The AdS/CFT idea emerged from developments in string theory and black hole thermodynamics in the 1990s. In the 1970s, studies of black hole entropy by Bekenstein and Hawking revealed that a black hole’s entropy is proportional to the area of its event horizon, not its volume, hinting that the information content of a region might reside on its surface. Building on this, 't Hooft and Susskind formulated the holographic principle: the maximal information (or entropy) inside a volume scales with the area of its boundary.[6] This principle suggested a radical way to reconcile quantum mechanics and gravity by reducing the effective degrees of freedom. Meanwhile, string theorists had found that certain configurations of D-branes could be used to count the microstates of black holes, reproducing the Bekenstein-Hawking entropy formula - a major success indicating that string theory knows about black hole thermodynamics. Maldacena’s insight was to consider the low-energy physics of a stack of D3-branes in two complementary ways: one way yields a gauge theory (a type of CFT) on the branes, and the other yields a supergravity (gravity) solution in the near-horizon region of those branes, which is AdS5 × S5.[2] He realized that these two descriptions must actually be the same physics - hence a duality between the gravity theory and the gauge theory. In essence, the holographic principle was realized in the context of string theory, tying together stringy descriptions of black holes and quantum field theories. Maldacena’s 1997 proposal thus grew directly out of attempts to understand black holes in string theory and gave precise form to Susskind’s holographic ideas. Leonard Susskind himself later remarked that Maldacena’s result brought the holographic principle “to center stage” by providing an actual working example.

AdS/CFT became a crucial element in the broader web of string theory dualities. In the mid-1990s, string theorists discovered that the five distinct string theories were related by dualities and were all part of a single 11-dimensional framework dubbed M-theory. The holographic duality fits naturally into this picture. For one, the AdS/CFT correspondence often involves M-theory backgrounds as well - for example, one version of AdS/CFT states that M-theory on AdS7 × S4 is dual to a 6-dimensional CFT (the so-called (2,0) theory). Another involves M-theory on AdS4 × S7 dual to a 3D superconformal field theory (known as the ABJM theory).[4] These examples show that the correspondence isn’t limited to the specific case Maldacena originally studied, but extends to other dimensions and systems, including those arising from M-theory. More generally, the success of AdS/CFT reinforced the idea that all consistent formulations of quantum gravity (such as string theories and M-theory) obey holographic dualities, differing perhaps only in details. It also hinted at a unifying principle: if every quantum gravity theory has an equivalent lower-dimensional description, holography might be a fundamental organizing principle of M-theory itself. Many theorists now suspect that the holographic principle is a fundamental pillar of M-theory and that AdS/CFT is one manifestation of a more general holographic framework uniting all string theories.

Conceptual Mechanics

Anti-de Sitter space is a model of a universe with constant negative curvature (the opposite of the positively curved de Sitter space that approximates our universe). In practice, AdS can be visualized in lower dimensions to build intuition. For example, a 2D AdS space can be thought of as a hyperbolic disk - a geometric surface where distances are defined in a funny way so that the edge of the disk is infinitely far away. If you “stack” such disks to add a time dimension, you get a cylinder-like AdS spacetime.[3] A key feature of AdS is that it has a boundary at spatial infinity. In AdS, unlike flat Minkowski space, signals or objects can reach the boundary in finite time, and the boundary acts like a timelike surface encasing the bulk. Intuitively, AdS space behaves somewhat like a gravitational “box” - its negative curvature tends to focus light and pull things back inward. A photon emitted from the center of AdS will travel outwards but eventually slow and return, as if there were reflecting walls at infinity. In contrast, Minkowski space (the flat spacetime of special relativity with zero curvature) has no boundary at infinity - an object can travel arbitrarily far away. And de Sitter (dS) space, with positive curvature (like an expanding sphere), doesn’t have a spatial boundary at infinity; instead it has horizons - one can only see out to a certain distance before space recedes too quickly. In de Sitter space (which resembles our universe with a positive cosmological constant), you cannot send a signal to “infinity” and back, whereas in AdS you effectively can due to its curved geometry. The exotic nature of AdS - a space where time and space are curved in strange ways - is crucial: it provides that outer boundary on which a dual CFT can live. In summary, AdS is a gravitational spacetime with a finite boundary that sits at infinity, enabling the peculiar setup of a holographic dual theory living on that boundary. Our real universe, by contrast, seems to be more like a de Sitter space, which is one reason why applying AdS/CFT to reality is non-trivial.

A conformal field theory is a type of quantum field theory (QFT) with extra symmetry: it is invariant under conformal transformations, which are essentially shape-preserving (angle-preserving) transformations including scaling. This means a CFT has no inherent length scale - if you zoom in or out, the physics looks the same. Such theories arise in various contexts: for example, the theory describing a system exactly at a critical phase transition in condensed matter physics is often a CFT (where it has scale invariance). In high-energy physics, an important example of a CFT is N=4 supersymmetric Yang-Mills theory in 4 dimensions, which is the prototype CFT in Maldacena’s duality.[5] It’s a gauge theory (somewhat like an idealized version of QCD without a scale that breaks conformal symmetry) and has a high degree of symmetry (super-symmetry and conformal symmetry). CFTs are “nice” QFTs in that they are often mathematically well-behaved and highly symmetric. In string theory, 2D conformal field theories also describe the worldsheet dynamics of strings. In AdS/CFT, the conformal field theory typically has one fewer spatial dimension than the AdS bulk. For instance, a 5D AdS bulk corresponds to a 4D CFT on its boundary. The significance of the CFT side is that it does not contain gravity - it’s an ordinary quantum field theory (e.g. a theory of particles and fields similar to the Standard Model, though with special symmetries). This is part of the magic: the correspondence says a quantum theory without gravity can be equivalent to a gravity theory, provided the spacetime is AdS. Importantly, many calculations that are hard to do directly in a strongly interacting field theory can become easier via the dual gravity description, and vice versa - the two sides complement each other.

The heart of AdS/CFT is the bulk-boundary correspondence: every phenomenon in the AdS bulk spacetime has a corresponding description on the boundary and vice versa. One useful analogy is to think of the boundary CFT as a kind of optical hologram of the bulk. Just as a 2D holographic plate encodes a 3D image, the 2D (or lower-dimensional) CFT encodes the 3D (or higher-dimensional) bulk physics.[7] To illustrate, Juan Maldacena described the duality in terms of “shadows”: the string theory in the interior of AdS has a “shadow” on the boundary which is the field theory. “Every fundamental particle in the interior has its counterpart on the boundary, and every interaction between interior particles corresponds exactly to an interaction between boundary particles,” Maldacena explains. If you drop an apple in the AdS bulk, an observer equipped with the boundary CFT could describe the apple’s fall entirely in boundary terms. In fact, one could “ignore the interior altogether without losing any information at all - this world is a true hologram.” The bulk gravity (including possibly curving spacetime, black holes forming, etc.) is encoded in the patterns of quantum fields on the boundary. The boundary is where the CFT lives, and it serves as the screen on which the bulk is projected. This means that if you know the state of the CFT exactly, you know everything about the AdS bulk state. Gravity, particles, even spacetime geometry in the AdS can be “read off” from the boundary data. In Maldacena’s toy model universe, gravity is an emergent illusion - it emerges for an observer in the bulk, but fundamentally all the dynamics can be described by a gravity-free quantum theory on the boundary. This bulk-boundary mapping is precise and quantitative in AdS/CFT. For example, one can compute how a disturbance in the CFT (say, injecting some energy at a certain point) corresponds to creating a particle that propagates in the AdS bulk.[2] Correlation functions in the CFT are related to interactions in the bulk, and the geometry of AdS itself is reflected in properties of the CFT. In short, the AdS/CFT correspondence provides a holographic “dictionary” translating bulk physics to boundary physics. This idea has deep implications: it suggests spacetime and gravity can be built out of more fundamental non-gravitational degrees of freedom on a lower-dimensional boundary. It’s a striking realization of the holographic principle and offers an entirely new perspective on what spacetime means in quantum gravity.

Physical Implications and Applications

AdS/CFT is a major step toward reconciling quantum mechanics with general relativity because it gives a concrete example of a quantum theory of gravity. On the AdS side, we have a gravity theory (often a low-energy limit of string theory) which is conjecturally exactly equivalent to the CFT, a standard quantum field theory. This means any question about quantum gravity (usually a very hard problem) can in principle be translated to a question about quantum field theory (which we understand much better in many cases).[5] It provides a non-perturbative definition of a quantum gravity theory: instead of trying to quantize gravity directly (which historically led to problems), AdS/CFT says “here is a gravity theory - it’s nothing but this well-defined quantum field theory, just rewritten.” In Maldacena’s model, the boundary CFT is a complete quantum description of everything happening in the bulk, including gravity. This example strongly suggests that gravity (at least in a negatively curved universe) does not contradict quantum mechanics - instead, it emerges from quantum mechanics in one lower dimension. For theoretical physicists, this was a proof-of-concept that the long-sought unification of quantum mechanics and general relativity is possible: one can have a theory that is simultaneously a quantum theory and equivalent to a classical gravity theory (in different regimes). It’s often said that in AdS/CFT, the gravitational force and spacetime curvature in the bulk are “coded” into the quantum behavior of the boundary fields, demonstrating how geometry can emerge from quantum degrees of freedom. This has fueled the idea that spacetime itself is emergent and fundamentally holographic. While AdS/CFT is a model and not our real universe, it offers a testing ground for quantum gravity ideas - a place where one can safely study and resolve conceptual problems that arise when combining GR and QM.

One of the most celebrated implications of AdS/CFT is in understanding black holes. In the duality, a black hole in the AdS bulk corresponds to a certain high-energy state (a thermal state) in the boundary CFT.[3] Thus, the mysterious thermodynamic properties of black holes can be translated into ordinary statistical physics of the CFT. For instance, the Bekenstein-Hawking entropy of a black hole (proportional to the horizon area) should equal the entropy of the corresponding ensemble of states in the CFT. Indeed, in many cases researchers have shown that the number of degrees of freedom in the CFT matches the area law, providing a microscopic explanation for black hole entropy. Rather than viewing a black hole as a breakdown of physics where information might be lost, AdS/CFT assures us that no information is actually lost. The black hole information paradox - the puzzle of whether information that falls into a black hole can ever get out - finds a natural resolution in AdS/CFT. From the boundary perspective, everything is manifestly unitary (quantum evolution on the boundary respects information conservation), so the formation and evaporation of a black hole in AdS must also be unitary.[6] As one physicist put it, “there is a dual description in which unitary evolution is automatic,” meaning that even though Hawking’s original calculations suggested information destruction, the dual CFT cannot lose information, so neither can the black hole. This convinced many that black holes do not actually destroy information and that any paradox is an artifact of viewing the process only from the gravity side. However, AdS/CFT does more than resolve the yes/no question of information loss - it provides tools to compute how information might be encoded in Hawking radiation in principle. Recent cutting-edge research into black hole evaporation and quantum entanglement (such as the calculation of the Page curve for an evaporating black hole) heavily relies on holographic ideas. The takeaway is that AdS/CFT bridges the gap between black hole physics and quantum physics, showing that black holes behave like ordinary quantum systems with a large number of degrees of freedom, thus demystifying many aspects of black hole thermodynamics and paradoxes.

One of the most profound developments spurred by AdS/CFT is the realization of a deep connection between quantum entanglement and spacetime geometry. In the duality, the structure of the AdS spacetime - essentially the shape of space, how it curves - is linked to how the quantum information is distributed in the CFT.[1] A famous result along these lines is the Ryu-Takayanagi formula (or conjecture), which proposes a precise quantitative relationship between the entanglement entropy of a region in the CFT and the area of a certain surface in the AdS bulk. In essence, if you take some portion of the CFT and compute how entangled it is with the rest of the system, that number equals the area (in Planck units) of a minimal surface that extends into the bulk AdS geometry. This is like a holographic version of the Bekenstein area-entropy connection, generalized to arbitrary systems, not just black holes. What this means conceptually is that the fabric of spacetime (in AdS) is woven from the entanglement structure of the CFT. If entanglement were to vanish, the spacetime might fall apart into disconnected pieces. This idea has led to slogans like “spacetime emerges from quantum entanglement.” Researchers have even found that the mathematics of AdS/CFT has similarities to quantum error-correcting codes, suggesting that the way information is protected in the bulk against loss (e.g., if part of the boundary is removed, the bulk still stays intact) works like an error-correcting code - an insight at the crossroads of quantum information and quantum gravity. All these developments indicate that AdS/CFT is teaching us why gravity has the form it does and how space, gravity, and quantum information are fundamentally related. It’s a new paradigm where geometry and quantum information are two sides of the same coin.

Even though AdS/CFT was discovered in the context of string theory, it has yielded surprising applications in various fields of physics - essentially exporting techniques from quantum gravity to solve problems elsewhere. A notable example is in nuclear physics: quark-gluon plasma (QGP), the hot dense soup of quarks and gluons created in heavy-ion colliders, is extremely strongly coupled and difficult to describe with normal QCD methods. Physicists found that using a 5D AdS gravity model dual to a 4D plasma-like CFT could give qualitative - and sometimes quantitative - insights into QGP properties.[4] In 2005, for instance, researchers applied AdS/CFT to calculate the ratio of shear viscosity to entropy density in a hot plasma. The result was a very small ratio, essentially a proposed universal lower bound. Experiments at RHIC and the LHC later measured the QGP’s viscosity and found it indeed is extraordinarily small, close to the predicted bound. Similarly, holographic models predicted a certain value for the jet quenching parameter (which measures how quickly high-energy quarks lose energy in the plasma) that turned out to be in the same ballpark as experimental results. These successes indicate that even though QGP is not literally SYM plasma, the AdS/CFT techniques capture essential physics of strongly coupled fluids.

In condensed matter physics, researchers have turned to AdS/CFT to tackle quantum systems that are strongly interacting, such as unconventional superconductors and quantum critical metals. This subfield is sometimes called “AdS/CMT” (for Condensed Matter Theory). The idea is to find an AdS dual for certain many-body systems. For example, a theory of electrons at a quantum critical point might map to some gravity theory with an extra dimension, where the formation of a superconducting phase corresponds to the formation of a particular field configuration in AdS (a “holographic superconductor”).[1] Indeed, holographic superconductors have been studied, where properties like the conductivity can be computed on the gravity side and compared to expectations for high-temperature superconductors. While this approach is more qualitative, it has provided new intuition - for instance, understanding how superconductivity might emerge from strong coupling in a dual picture. More generally, exotic phases like non-Fermi liquids and superfluids have been modeled with AdS duals, offering a new toolkit to condensed matter theorists.

AdS/CFT ideas have even infiltrated quantum information theory and quantum computing. The correspondence’s implications about entanglement and error correction have led to fruitful dialogues between these fields. Concepts like tensor networks (MERA) used in quantum information to efficiently represent strongly correlated states have been found to have similarities with the spatial structure of AdS space, hinting that they are like discrete holographic duals. This has led to quantum information scientists using holographic systems as testing grounds for ideas about quantum entanglement, complexity, and information scrambling. For example, how fast quantum information spreads (or scrambles) in a black hole has a dual description in the CFT, linking to quantum chaos and even to ideas of computational complexity in quantum circuits.[7] Such cross-disciplinary applications of AdS/CFT are still developing, but they underscore a key point: AdS/CFT is not just about quantum gravity - it’s a powerful toolkit. It allows researchers to translate problems in one realm to another where they might be easier to solve. This dual perspective has provided insights into phenomena as diverse as the viscosity of fluids, the resistance of superconductors, and the entanglement structure of quantum states, truly bridging high-energy physics with low-energy quantum physics.

Open Questions and Interpretational Challenges

A fundamental limitation of the AdS/CFT correspondence is right in its name - the “AdS.” Our real universe, as far as observations indicate, has a positive cosmological constant and is expanding (accelerating, in fact), which means its large-scale geometry is closer to de Sitter (dS) space, not Anti-de Sitter. In de Sitter space, there is no timelike boundary at spatial infinity where one could easily imagine a CFT living; instead, de Sitter has horizons and a future boundary that is a moment in time. This raises the question: Does a correspondence like AdS/CFT exist for de Sitter space? And if not, what does that mean for applying holography to our cosmos?[5] So far, AdS/CFT has been firmly established only for negatively curved spacetimes. It is not proven whether a similar duality holds for a universe like ours. In fact, Maldacena’s original work explicitly assumed an AdS5 background with supersymmetry and other ideal conditions, which do not match reality. Researchers have written thousands of papers extending and exploring AdS setups, but the fact remains: our universe is not AdS. This is sometimes called the “cosmological constant problem” for holography - we don’t know how to deal with a positive cosmological constant in the same way. The consequence is that AdS/CFT, while immensely powerful theoretically, might be describing toy models of universes rather than our own universe. That said, some physicists remain optimistic that lessons from AdS will carry over, at least approximately, to gravity in our universe, or that a yet-to-be-found holographic dual for de Sitter space might exist.

Motivated by the success of AdS/CFT, there have been attempts to formulate a de Sitter/Conformal Field Theory correspondence (dS/CFT). Notably, in 2001, Andrew Strominger proposed a heuristic dS/CFT analogy, suggesting that quantum gravity on a de Sitter space might be dual to a CFT defined on the future boundary of that space (a spacelike surface at infinity).[6] In this picture, time itself in the bulk would emerge from the RG flow (scale transformations) of the boundary theory. However, constructing a concrete example of dS/CFT has proven challenging. One big issue is that we lack a controlled example of de Sitter space in string theory - most solutions of string theory with positive cosmological constant are unstable or poorly understood. Without a solid “gravity side” to start from, it’s hard to find the dual field theory. Another issue is that any would-be CFT dual to dS might have strange properties: for instance, studies indicate it might have an imaginary central charge (related to being non-unitary), suggesting that the usual rules of unitary quantum field theory might not apply. In other words, a naive dS/CFT dual could be a non-unitary CFT, which is a significant departure from the well-behaved unitary CFTs in AdS/CFT. These and other technical obstacles mean dS/CFT remains a conjectural, much less developed idea. It’s an area of ongoing research - a dS/CFT correspondence, if discovered, would be revolutionary as it could directly apply holography to cosmology (potentially explaining inflation or horizon entropy in a dual way). For now, though, it’s fair to say we don’t yet have a holographic duality for de Sitter space that rivals the clarity and evidence of AdS/CFT. Our current holographic theories seem to prefer a universe with a “negative” vacuum energy. This mismatch with reality is a humbling reminder of the limits of our theoretical tools.

There is also a philosophical and practical debate about how “real” AdS/CFT is. On one hand, the duality is supported by a great deal of evidence - countless checks have been made in various limits, and no contradictions have been found.[4] Many physicists take it as established (within string theory) that the correspondence is true for the examples studied, even if a rigorous mathematical proof is absent. On the other hand, AdS/CFT is still a conjecture - by necessity, since we don’t yet have a non-perturbative definition of string theory to prove the equivalence from first principles. It’s a striking example of where physics intuition and consistency checks outran mathematical rigor. There’s also the fact that AdS/CFT relates to a fictional universe (one with AdS boundary conditions and often supersymmetry) rather than the observable universe. This means direct experimental verification in the traditional sense is not possible - we cannot set up a four-dimensional supersymmetric Yang-Mills theory on a bench, let alone a five-dimensional AdS gravity region to compare it with. However, the usefulness of AdS/CFT can be indirectly tested by how well it predicts or explains phenomena in systems we can experiment on. As discussed, the correspondence has had successes in predicting properties of the quark-gluon plasma that were later observed. These successes give some credence to the idea that the holographic principle captures something real about strongly-coupled physics, even if our universe isn’t exactly AdS. Still, skeptics might argue that using AdS/CFT to model QGP or superconductors is like using an idealized model - it doesn’t prove the duality fundamental, it just shows it’s a useful calculus trick in those cases. Another angle on “experimental” tests is quantum simulation: some have pondered whether quantum computers or analog lab systems could be used to simulate a CFT and thereby “observe” the dual AdS physics indirectly, but this is in very early stages.

In terms of conceptual reality, a question often asked is: Is AdS/CFT just a mathematical equivalence, or is the boundary CFT actually how nature stores information about the bulk? If we had an AdS universe in a box, would the boundary literally have the degrees of freedom for everything inside it? The conservative view is that AdS/CFT is a powerful theoretical correspondence - a tool that, while not directly testable, is likely true and part of the consistency of string theory.[2] A more radical view (espoused by some) is that the duality hints at a paradigm where our world could be holographic in a similar way - that the ultimate description of our universe might be a quantum theory without gravity in one lower dimension. Maldacena himself has said we should take the idea seriously until proven otherwise. At the moment, AdS/CFT stands as a monumental theoretical discovery that has passed many consistency tests and has become a cornerstone of modern theoretical physics, yet it also remains, in a sense, unverified by direct experiment and unproven by rigorous mathematics. It straddles the line between physics and mathematics, offering profound insights but also leaving us with deep questions: How far does holography extend? Is spacetime fundamentally holographic even in a non-AdS context? Could we find a way to experimentally access higher-dimensional gravity through its lower-dimensional dual (for example, using condensed matter experiments or quantum simulators)? These questions drive ongoing research.

Conclusion

In summary, the AdS/CFT correspondence has transformed theoretical physics by providing a tangible example of holography. It rests on fundamental principles that tie gravity to quantum field theory, emerged from attempts to solve puzzles in black hole physics, and operates through a precise bulk-boundary mapping that challenges our understanding of space and information. It has illuminated aspects of quantum gravity, shed light on black hole information and entropy, and reached into other fields for practical insights. Yet, it also faces limitations - chiefly that our real universe isn’t AdS - and it remains an unproven but exceedingly well-motivated idea. As research progresses, physicists continue to test the edges of AdS/CFT, searching for generalizations (like dS/CFT) and thinking of clever ways to verify its implications. Whether or not our world is a hologram in the AdS/CFT sense, the correspondence stands as a powerful reminder that our universe’s deepest laws might have dual interpretations, and that understanding gravity may require us to think in terms of holograms and dimensions beyond the immediately visible. The AdS/CFT duality has opened a window into a new way of thinking about reality - one where gravitational worlds and quantum fields are just different languages describing the same underlying truth.

References

- 1.Beisert, N., Ahn, C., Alday, L. F., Bajnok, Z., Drummond, J. M., Freyhult, L., Gromov, N., Janik, R. A., Kazakov, V., Klose, T., & Korchemsky, G. P. (2012). Review of AdS/CFT integrability: An overview. Letters in Mathematical Physics, 99, 3-32. ↩

- 2.Berenstein, D. (2004). A toy model for the AdS/CFT correspondence. Journal of High Energy Physics, 2004(07), 018. ↩

- 3.Ramallo, A. V. (2015). Introduction to the AdS/CFT correspondence. In Lectures on Particle Physics, Astrophysics and Cosmology: Proceedings of the Third IDPASC School, Santiago de Compostela, Spain, January 21-February 2, 2013 (pp. 411-474). Springer International Publishing. ↩

- 4.Klebanov, I. R., & Witten, E. (1999). AdS/CFT correspondence and symmetry breaking. Nuclear Physics B, 556(1-2), 89-114. ↩

- 5.Hubeny, V. E. (2015). The AdS/CFT correspondence. Classical and Quantum Gravity, 32(12), 124010. ↩

- 6.Năstase, H. (2015). Introduction to the AdS/CFT Correspondence. Cambridge University Press. ↩

- 7.Zaffaroni, A. (2000). Introduction to the AdS-CFT correspondence. Classical and Quantum Gravity, 17(17), 3571. ↩