In string theory, a D-Brane (short for Dirichlet membrane) is an extended object – essentially a membrane-like surface – within the higher-dimensional space of the theory on which open strings can end. The “D” reflects the Dirichlet boundary condition that the string’s endpoints satisfy, a concept named after the mathematician J. P. G. Lejeune Dirichlet.[10] In simple terms, a D-brane is a region in space where the endpoints of an open string are anchored or pinned down, rather than freely moving through space. This idea emerged when physicists realized that the ends of open strings weren’t just floating in space – it was as if they were tied to something, a surface or object that wasn’t originally part of early string theory. D-Branes were introduced to provide those “anchor” surfaces, and it turned out that these objects were not only possible but necessary for a consistent theory. In fact, when Joseph Polchinski and collaborators formalized D-branes around 1989, they discovered that D-branes are an intrinsic feature of string theory rather than an optional add-on.[5] They carry energy and can even produce gravitational effects like ordinary mass. D-branes are typically classified by their spatial dimensionality: for example, a D0-brane is like a point particle, a D1-brane is a one-dimensional filament (a “D-string”), a D2-brane is a two-dimensional sheet or membrane, and so on. In superstring theories (which live in 10 spacetime dimensions), D-branes can have up to 9 spatial dimensions (plus time), while in the simpler 26-dimensional bosonic string theory one can have even higher-dimensional D25-branes filling space.[10] The key insight is that open strings must end on D-branes: the brane provides the “home” for string endpoints. This was a revolutionary realization that launched what’s known as the second superstring revolution in the mid-1990s, reshaping our understanding of string theory’s ingredients.[5]

Physical Interpretation – Branes as Cosmic Membranes

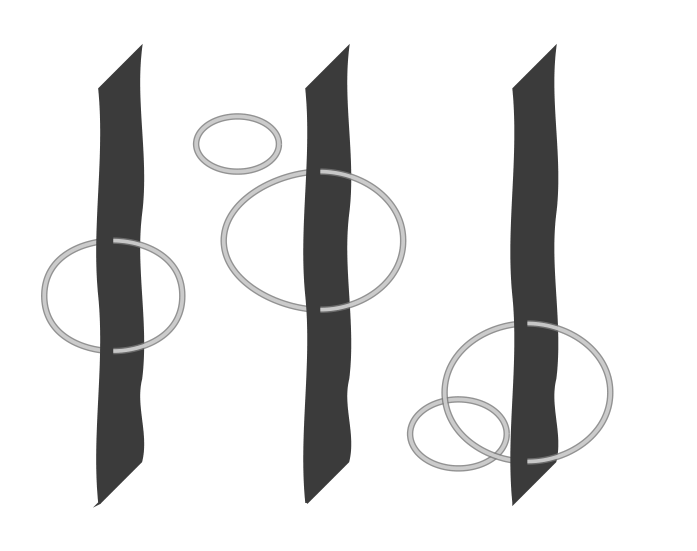

One intuitive way to picture D-branes is to think of familiar membranes or surfaces in everyday life. Imagine a thin soap film spread across a wire frame: the film is a two-dimensional surface embedded in our three-dimensional world. In string theory, a D-brane is analogous to such a film (though it can have more than two dimensions) existing in a higher-dimensional space. Just as a soap film can be flat or curved, a D-brane can take on various shapes – it might stretch out infinitely flat, or form a curved shape like a bubble. In fact, a D2-brane (two spatial dimensions) could be spherical “like a soap bubble,” or it could be an endless flat sheet. The crucial property of a D-brane is that open strings attach to it. If you think of a closed string as a tiny loop (like a rubber band in its closed ring shape), an open string is like a rubber band cut open into a line segment. Those cut ends must stick to a D-brane’s surface. By contrast, closed strings (loops) are not tied down – they can drift away from the brane into the higher-dimensional “bulk” space. In this sense, a D-brane functions like a kind of cosmic Velcro or sticky surface for string endpoints. To use another metaphor, you can picture an insect walking on the surface of water: the water’s surface is like a brane, restricting the insect’s motion to two dimensions, and preventing it from moving vertically off the surface. Similarly, standard particles and forces (those represented by open strings) might be confined to a D-brane representing our observable universe, unable to leave it. Only certain modes like gravity (carried by closed strings, analogous to waves in the water) can propagate off the brane. These analogies capture how D-branes act as membranes in higher-dimensional space, providing a vivid mental image of their role in string theory’s geography.[6]

Types of D-Branes and Their Dimensionality

D-branes come in various types distinguished by their dimensionality. The number after the “D” in Dp-brane denotes the number of spatial dimensions the brane has. For instance, a D0-brane has 0 spatial dimensions – it is essentially a point-like object (localized in space, like a particle). A D1-brane is one-dimensional, often referred to as a “D-string,” which is a line-like object (it’s actually a string that is itself a brane!). A D2-brane extends in two dimensions like a flat sheet or membrane. Continuing this pattern, a D3-brane extends in three spatial dimensions (like a 3D volume), and so on up to D9-branes which fill nine spatial dimensions. In 10-dimensional superstring theory, a D9-brane is the highest-dimensional brane, essentially filling all of space (for example, Type I string theory includes space-filling D9-branes as part of its consistent setup). There are even D(−1)-branes, called D-instantons, which are peculiar objects localized in both space and time – effectively zero-dimensional in space and existing for an instant in time, but these are more exotic and act more like events than extended objects. The existence of this whole “spectrum” of -branes (for p = –1, 0, 1, 2, … 9 in superstrings) means string theory isn’t just a theory of one-dimensional strings; it also contains higher-dimensional membranes as fundamental ingredients. Different string theories permit different sets of D-branes: for example, Type IIA string theory contains only even-dimensional D-branes (D0, D2, D4, etc.), while Type IIB contains odd-dimensional ones (D1, D3, D5, etc.), due to the way the theory’s symmetries work.[11] But regardless of type, the concept is similar – a Dp-brane has p spatial dimensions and provides a platform for strings to end. It’s worth noting that our observable Universe could itself be a D3-brane in a higher-dimensional space: three familiar spatial dimensions where standard particles roam, with additional hidden dimensions that we don’t directly see because we (and all the particles we can detect) are stuck on the brane.[9] We will explore this idea more in a later section, as it offers a compelling explanation for why extra dimensions might be hidden from us.

Why D-Branes Are Essential in String Theory?

D-branes are not just optional add-ons; they play a central role in string theory’s dynamics. One reason is that they are required for consistency whenever open strings are present. In earlier string theory models, physicists often considered only closed strings (loops) to avoid the issue of what happens at an open string’s end. However, real-world forces (like electromagnetism or the nuclear forces) would be mediated by open strings in string theory models, so open strings are important to include. A D-brane provides the boundary conditions needed for open strings – in essence, an open string’s ends must lie on a D-brane. Without D-branes, open strings wouldn’t have a home, and the theory would be inconsistent.[1]

Equally important, D-branes give rise to rich physics on their surfaces. An open string attached to a D-brane can vibrate in various ways, and those vibrations appear, to an observer confined on the brane, as different particle types. Notably, the lowest-energy vibrations of open strings look like gauge particles – the carriers of forces. In fact, a single D-brane naturally gives rise to a U(1) gauge theory (similar to electromagnetism) on its world-volume. If you have multiple D-branes, even more interesting things happen: strings can stretch from one brane to another, and the variety of endpoints effectively behaves like multiple charge types, yielding a larger gauge symmetry.[7] For example, a stack of coincident D-branes (all sitting on top of each other) produces a U() gauge theory on the brane collection. This means D-branes provide a natural way to realize the kind of gauge theories that describe elementary particles. The electric and color forces in our universe are described by gauge theories (with symmetry groups like U(1), SU(2), SU(3)), and string theory beautifully accommodates this by simply having multiple branes: an open string with one end on Brane #1 and the other on Brane #2 might represent a particle carrying charge under the corresponding gauge fields. In essence, D-branes put the “force” in string theory – they support the fields that we identify as photons, gluons, W/Z bosons, etc., depending on how the branes are arranged. This was a profound insight because it unified two previously separate domains: string theory (a candidate theory of quantum gravity) and gauge theory (the language of the Standard Model of particle physics).

Moreover, D-branes are dynamic objects themselves. Initially one might imagine a D-brane as a fixed, rigid hypersurface. But in string theory, branes can move and fluctuate. The open strings attached to a D-brane include modes that correspond to the brane’s own vibrations and position. A D-brane can wiggle like a sheet in the wind, oscillate, or even recoil if a string pulls on it. They also carry energy (proportional to their tension) and so gravitate – a D-brane has a gravitational field, and multiple branes can attract or repel each other via the exchange of closed strings (gravitons).[6] In fact, when two D-branes approach each other, strings stretching between them can be created or excited, effectively mediating a force between the branes. D-branes can even bind together or annihilate in certain circumstances (in processes related to brane-antibrane pairs and tachyon condensation, which is a mechanism where unstable branes can dissolve into stable ones).[11] All of this dynamism means D-branes participate actively in the physical processes of string theory – they aren’t passive backgrounds but objects that obey physical laws. As one physicist memorably put it, D-branes are “as real, and just as important, as the strings themselves!”.[2] This realization has allowed string theorists to construct toy models of our universe where everything we know (except gravity) is confined to a 3-dimensional D-brane, while gravity seeps into the extra dimensions – offering possible answers to long-standing puzzles like why gravity is so much weaker than other forces.

Connections to Black Holes and Gravity

One of the most remarkable developments involving D-branes is how they illuminate the nature of black holes and gravitation in string theory. In 1995, Polchinski made a breakthrough by showing that D-branes are the carriers of a certain type of charge (Ramond–Ramond charge) in string theory, and that a stack of D-branes is physically equivalent to a classical black brane solution in higher-dimensional general relativity.[5] In simpler terms, a D-brane with many open strings attached to it has a gravitational pull and other properties very much like an extremal black hole. This insight was crucial because it provided the first solid link between the ephemeral world of strings and the concrete physics of a gravitating object. D-branes, being heavy and charged, warp the spacetime around them – if you pile enough of them together, you effectively create something with an event horizon. Polchinski’s result triggered what’s now called the holographic revolution, leading to ideas that the behavior of gravity (a spacetime phenomenon) can be encoded by the physics of D-branes (a lower-dimensional, non-gravitational system).

Perhaps the greatest triumph of D-brane physics was solving a long-standing puzzle about black holes: the origin of black hole entropy. Classically, a black hole’s entropy (as given by the Bekenstein–Hawking formula) is proportional to the area of its event horizon, but what microphysical states does this entropy count? In 1996, string theorists Andrew Strominger and Cumrun Vafa used D-branes to answer this question for certain extremal black holes.[3] They considered a particular configuration of D-branes (specifically D5-branes and D1-branes, among others) that, from afar, looks like a single black hole. By counting the myriad ways open strings could vibrate and arrange on this D-brane system – essentially counting the quantum states of the D-branes and strings – they found a number of microstates that exactly matched the Bekenstein–Hawking entropy of the corresponding black hole.[12] This was a stunning result: it was the first statistical-microphysical derivation of a black hole’s entropy within a candidate theory of quantum gravity. The D-brane picture thus provided the “missing degrees of freedom” that a black hole needs to have entropy. These states are sometimes described heuristically as open strings and branes in bound states that, when coarse-grained, look like a smooth black hole. Although Strominger and Vafa’s calculation applied to highly supersymmetric and special cases (far from the typical black holes formed by collapsing stars), it gave a profound credibility to string theory – showing that it can, in principle, reconcile gravity with quantum mechanics by explaining black hole properties.

D-branes have also shed light on the holographic principle and the idea that gravity and spacetime might emerge from lower-dimensional physics. A key insight here is the notion of open/closed string duality: an interaction between D-branes can be viewed in two complementary ways – either as two branes exchanging a closed string (a graviton, for example) between them, or as a single open string stretching between the branes forming a loop. Polchinski’s work showed that the gravitational attraction of a brane (a closed-string effect in spacetime) is dual to the vibrational modes of open strings on the brane (a gauge force effect on the brane). This duality of perspectives is at the heart of holography. It suggests that a gravitating system in the “bulk” (like a black hole) can be described by a gauge theory living on the “boundary” (like a set of D-branes). In the D-brane context, this culminated in the famous AdS/CFT correspondence (Anti-de Sitter/Conformal Field Theory duality). In AdS/CFT, a stack of D3-branes is used to generate a particular higher-dimensional spacetime (AdSS geometry), and string theory on that curved spacetime is found to be dual to a conformal gauge theory (known as super Yang–Mills) living on the D3-branes’ 4-dimensional world-volume.[8] Essentially, the gravitational physics in the vicinity of the branes is equivalent to the quantum field theory on the branes. This idea was first conjectured by Juan Maldacena in 1997 and has been extensively tested in theoretical calculations since.[4] The D-branes were the crucial ingredient that made this possible: because they can be studied as physical objects with open-string fields (a gauge theory) and also as sources of geometry (a gravity theory), they are the “bridge” allowing one to translate between the language of gravity and the language of particle physics. AdS/CFT and related D-brane dualities have shown that holography – the encoding of a higher-dimensional gravity theory in a lower-dimensional non-gravitational theory – is not just science fiction, but a concrete principle, with D-branes providing explicit examples of how it works.

To gain a little more intuition about the AdS/CFT correspondence, one can imagine a video game on a 2D screen that perfectly simulates a 3D world. The actual physics of the game (textures, motion, interactions) happen on the flat screen, yet they represent a full 3D world. AdS/CFT suggests something similar: a world with gravity and extra dimensions can be fully described by a lower-dimensional theory without gravity. In short, the universe may be a hologram—a higher-dimensional world can emerge from a lower-dimensional quantum theory.

Real-World Applications and Theoretical Insights

Beyond their importance in pure theory, D-branes have influenced many ideas about our real universe. One prominent idea is the brane-world scenario in cosmology.[9] If there are extra spatial dimensions beyond the three we experience, one elegant way to hide them (and explain why we don’t see or move through them) is to suppose that we are stuck on a 3-dimensional D-brane – essentially, our universe is a D3-brane floating in a higher-dimensional “bulk.” In this picture, all ordinary matter and light consist of open strings with ends tied to our brane, so they cannot escape into the extra dimensions. Forces like electromagnetism and the nuclear forces would be confined to our 3-brane, which is why we don’t detect any extra dimensions in everyday life – we simply can’t step off our membrane. Gravity, however, is different: the graviton is a closed string, and closed strings are not bound to branes. They can propagate in the extra dimensions. This could explain why gravity is so weak compared to other forces: it dilutes itself by spreading out into the unseen dimensions orthogonal to our brane, whereas the other forces are stuck on the brane and thus concentrated.

The braneworld picture, inspired by D-branes, provides intuitive solutions to puzzles like the hierarchy problem (why gravity is exponentially weaker than electromagnetism) by envisioning scenarios where gravitational field lines “leak” off our brane into the extra dimensional bulk. In fact, proposals such as the Randall–Sundrum model leverage branes to explain gravity’s weakness by warping the extra dimension and confining gravity in a certain way – an idea that has its conceptual origins in D-brane physics.[9]

Braneworld cosmology also opens the door to imaginative new explanations of cosmic events. For example, the Big Bang itself has been theorized in some models to be the result of a collision between two branes.[13] In these “ekpyrotic” or cyclic universe scenarios, our brane and another parallel brane drift through an extra dimension, eventually crashing together – the tremendous energy of that collision is what we perceive as the Big Bang, and the branes then rebound or separate, with their vibrations creating the matter and radiation in our universe. Similarly, brane inflation scenarios imagine that the rapid inflationary expansion of our early universe was driven by the motion of branes: as a D-brane and an anti-D-brane pulled towards each other and eventually annihilated, the process released a huge amount of energy, driving exponential expansion and reheating the universe.[13] While these ideas are speculative, they show how D-branes have provided fresh ways to think about old problems in cosmology (offering alternatives or supplements to traditional inflation, for instance). Importantly, some of these braneworld ideas lead to distinctive predictions – for example, the existence of extra dimensions might be probed by deviations from Newton’s gravity at sub-millimeter distances, or by microscopic black holes that could be produced in high-energy collisions. Experiments have tested gravity down to very short scales (on the order of tens of microns) and so far found no deviation from the expected laws, putting constraints on the size or warping of any extra dimensions. Still, the allure of a braneworld – a universe on a membrane – remains, and researchers continue to refine these models.

In the realm of particle physics, D-branes have become a toolkit for model-building. String phenomenologists (physicists trying to connect string theory to the actual Standard Model of particles) often use configurations of intersecting D-branes to produce gauge theories that resemble the Standard Model. For instance, one can arrange stacks of D-branes such that their intersection points yield the quarks and leptons we observe, with strings stretching between different stacks behaving like the force carriers.[7] An open string connecting two different brane stacks might be interpreted as a particle transforming under two different gauge groups – exactly what is needed for modeling quarks (which feel both the electromagnetic and strong forces, for example). By engineering the geometry and intersection of branes in a compactified extra-dimensional space, physicists have created candidate models with three families of particles, the correct gauge symmetry structure, etc. While no model is yet perfect or fully realistic, this D-brane engineering of gauge theories has generated a huge number of semi-realistic scenarios to explore, showing that string theory in principle has the ingredients to incorporate all of known particle physics. In addition, D-branes have shed light on pure theoretical aspects of quantum field theory itself. They provide a natural home for objects like magnetic monopoles and instantons – soliton solutions in gauge theories – which appear as certain configurations of D-branes (for example, a D1-brane stretching between D3-branes can realize a ’t Hooft–Polyakov monopole in the worldvolume theory). Branes have also been used to derive and visualize dualities between field theories. A famous example is Seiberg duality in supersymmetric QCD, which can be understood by moving branes around in a particular setup (the so-called Hanany–Witten brane configurations).[14] This cross-pollination between string theory and field theory means developments in D-brane physics often translate into new insights in gauge theories, and vice versa.

Latest Research and Developments

Research into D-branes remains a vibrant and evolving field, continually yielding new insights in both physics and mathematics. One active area is the study of quantum aspects of black holes using D-branes.[15] The initial entropy calculations by counting D-brane states have blossomed into a broader effort to understand the interior of black holes and the information paradox.[12] Some proposals (like the fuzzball theory) suggest that what we think of as a “black hole” might actually be an ensemble of D-brane and string configurations with no traditional singularity or empty interior – essentially, that a black hole is a very large, complex D-brane bound state.[15] Recent work investigates how close these stringy microstates can come to forming something like a real black hole and how they might resolve the paradox of information loss. D-branes also feature prominently in studies of holography beyond AdS/CFT, for example in lower-dimensional dualities or cases with fewer symmetries. Physicists are trying to apply the holographic principle (born from D-brane studies) to more realistic settings – such as confining gauge theories similar to quantum chromodynamics (QCD) or to strange states of matter in condensed matter physics. These efforts often involve adding various types of D-branes to an AdS setup (for instance, adding D7-branes to introduce flavor quarks in holographic QCD, or using D-branes to model defects/surfaces in a dual field theory). The result has been a kind of holographic laboratory where researchers use brane setups to mimic properties of real materials, like superconductors or superfluids, shedding light on strongly coupled electronics systems by studying a dual gravitational problem.

On the mathematical side, D-branes have become central in areas like mirror symmetry and algebraic geometry. Mathematicians study D-branes as objects in something called the derived category of coherent sheaves (in Type II string compactifications) – effectively linking branes to complex geometry and topology.[16] Discoveries about how branes can wrap cycles in extra dimensions have led to advances in pure math, such as the concept of bridgeland stability (inspired by brane stability conditions) and insights into enumerative geometry (like counting curves on Calabi–Yau spaces via “BPS state counting,” where branes again play a role). Even quantum information theory is finding a connection: ideas from D-brane physics and AdS/CFT are being used to understand quantum entanglement and error-correcting codes, with the bulk-boundary relationship of holography serving as a guiding analogy for how information might be geometrically organized.

In more concrete terms, ongoing research often involves studying novel D-brane configurations and their dynamics. For example, scientists examine what happens when D-branes move at nearly the speed of light, or how branes nucleate and evaporate. There are studies of time-dependent brane solutions (important for cosmology – e.g. could a brane spontaneously form or dissolve over time?) and of the role of D-branes in “stringy” phase transitions. One recent line of inquiry looks at how black holes in Anti-de Sitter space can radiate by emitting D-branes – a hybrid process of Hawking radiation and brane dynamics – to better understand black hole evaporation in a controlled setting. Another development is the use of D-branes in the so-called swampland program, which aims to distinguish which low-energy theories can come from a consistent string theory with branes (the “landscape”) and which are impossible to get (the “swampland”). D-brane consistency conditions (like anomaly cancellation and charge quantization in K-theory) provide powerful constraints on would-be theories of physics.

Conclusion

After decades of study, D-branes remain a cornerstone of modern theoretical physics. They tie together disparate concepts – from the stretching of a fundamental string to the evaporation of a black hole – into a single framework. What makes them especially compelling is how they allow complex, higher-dimensional phenomena to be described in simpler, lower-dimensional terms. By thinking in terms of D-branes, physicists have found new ways to describe our universe: as a membrane with hidden dimensions, as a hologram encoded on a distant boundary, or as a network of vibrating strings whose collective behavior gives rise to gravity and particles. As research continues, D-branes will undoubtedly continue to be the source of both revolutionary ideas and deep unifying principles, illustrating the power of string theory to connect the seen and the unseen in our quest to understand the cosmos.

References

- 1.Bachas, C. P. (1998). Lectures on D-branes. arXiv:hep-th/9806199. ↩

- 2.Hashimoto, K. (2012). D-Brane: Superstrings and New Perspective of Our World. Springer. ISBN 978-3-642-23573-3. ↩

- 3.Strominger, A., & Vafa, C. (1996). Microscopic origin of the Bekenstein-Hawking entropy. Physics Letters B, 379(1-4), 99-104. ↩

- 4.Maldacena, J. (1999). The large-N limit of superconformal field theories and supergravity. International Journal of Theoretical Physics, 38(4), 1113-1133. ↩

- 5.Polchinski, J. (1995). Dirichlet Branes and Ramond-Ramond Charges. Physical Review Letters, 75(26), 4724-4727. ↩

- 6.Johnson, C. V. (2003). D-branes. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-80912-3. ↩

- 7.Witten, E. (1996). Bound states of strings and p-branes. Nuclear Physics B, 460(2), 335-350. ↩

- 8.Aharony, O., Gubser, S. S., Maldacena, J., Ooguri, H., & Oz, Y. (2000). Large N field theories, string theory and gravity. Physics Reports, 323(3-4), 183-386. ↩

- 9.Randall, L., & Sundrum, R. (1999). A large mass hierarchy from a small extra dimension. Physical Review Letters, 83(17), 3370-3373. ↩

- 10.Polchinski, J. (1998). String Theory, Volume 1: An Introduction to the Bosonic String. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-67227-6. ↩

- 11.Douglas, M. R. (1995). Branes within branes. arXiv:hep-th/9512077. ↩

- 12.Horowitz, G. T., & Strominger, A. (1996). Counting states of near-extremal black holes. Physical Review Letters, 77(12), 2368-2371. ↩

- 13.Dvali, G., & Tye, S. H. (1999). Brane inflation. Physics Letters B, 450(1-3), 72-82. ↩

- 14.Giveon, A., & Kutasov, D. (1999). Brane dynamics and gauge theory. Reviews of Modern Physics, 71(4), 983-1084. ↩

- 15.Mathur, S. D. (2005). The fuzzball proposal for black holes: An elementary review. Fortschritte der Physik, 53(7-8), 793-827. ↩

- 16.Aspinwall, P. S. (2004). D-branes on Calabi-Yau manifolds. arXiv:hep-th/0403166. ↩