Calabi-Yau manifolds are special multidimensional geometric shapes that play a key role in both advanced mathematics and theoretical physics. In essence, a Calabi-Yau manifold is a space with no intrinsic curvature and a high degree of symmetry, despite its complex shape. Mathematically, these manifolds were first studied in the context of complex differential geometry, and later they gained fame for providing a possible blueprint for the “hidden” extra dimensions in string theory. They are named after mathematicians Eugenio Calabi and Shing-Tung Yau - Calabi proposed their defining properties in the 1950s, and Yau proved a crucial theorem about their existence in the 1970s. Today, Calabi-Yau spaces are known for their unique geometric features, their Ricci-flat nature (meaning they have no overall curvature), and their special holonomy (a kind of symmetry in how they twist), all of which make them essential in efforts to unify gravity with the other fundamental forces of nature.

Background and Historical Development

The concept of Calabi-Yau manifolds emerged from problems in complex differential geometry. In 1954, Eugenio Calabi conjectured that certain complex spaces could be endowed with a metric (a way of measuring distances) that has zero Ricci curvature - essentially a flat curvature in the Einsteinian sense.[1] This idea, known as the Calabi conjecture, meant that if a complex manifold met certain criteria (technically, having a “vanishing first Chern class,” which is a topological condition), then it should be possible to shape it so that it has no internal curvature (Ricci-flatness). For over two decades, this conjecture remained unproven, intriguing mathematicians and hinting at deep connections between geometry and physics.

In the 1970s, Shing-Tung Yau took on Calabi’s challenge. In 1976, Yau succeeded in proving the Calabi conjecture, demonstrating rigorously that such Ricci-flat metrics do exist on the proposed class of complex manifolds.[2] This monumental proof earned Yau a Fields Medal and transformed what were once theoretical shapes into concrete mathematical objects. With Yau’s achievement, the special class of compact Kähler manifolds with vanishing Ricci curvature was shown to be real, and these manifolds were thereafter named Calabi-Yau manifolds in honor of Calabi’s vision and Yau’s proof. Yau’s result assured mathematicians and physicists that these peculiar “flat” yet compact spaces are not just abstract fantasies, but actually possible according to the rules of geometry.

The timing of Yau’s work coincided with developments in theoretical physics. In 1985, physicists Philip Candelas, Gary Horowitz, Andrew Strominger, and Edward Witten famously incorporated Calabi-Yau manifolds into string theory, coining the term “Calabi-Yau manifold” for physics use.[3] This was during the so-called “First Superstring Revolution,” when string theory - a candidate for a unified theory of all fundamental forces - was gaining momentum. The emergence of Calabi-Yau geometry provided exactly what string theorists needed: a way to hide extra dimensions of space in a consistent manner. Thus, a concept born in pure mathematics found a natural home in cutting-edge physics. The historical development of Calabi-Yau manifolds is a prime example of how abstract mathematical ideas (like Calabi’s conjecture) can later become crucial components of physical theory, underscoring a deep unity between math and the laws of nature.

Geometric Characteristics and Key Properties

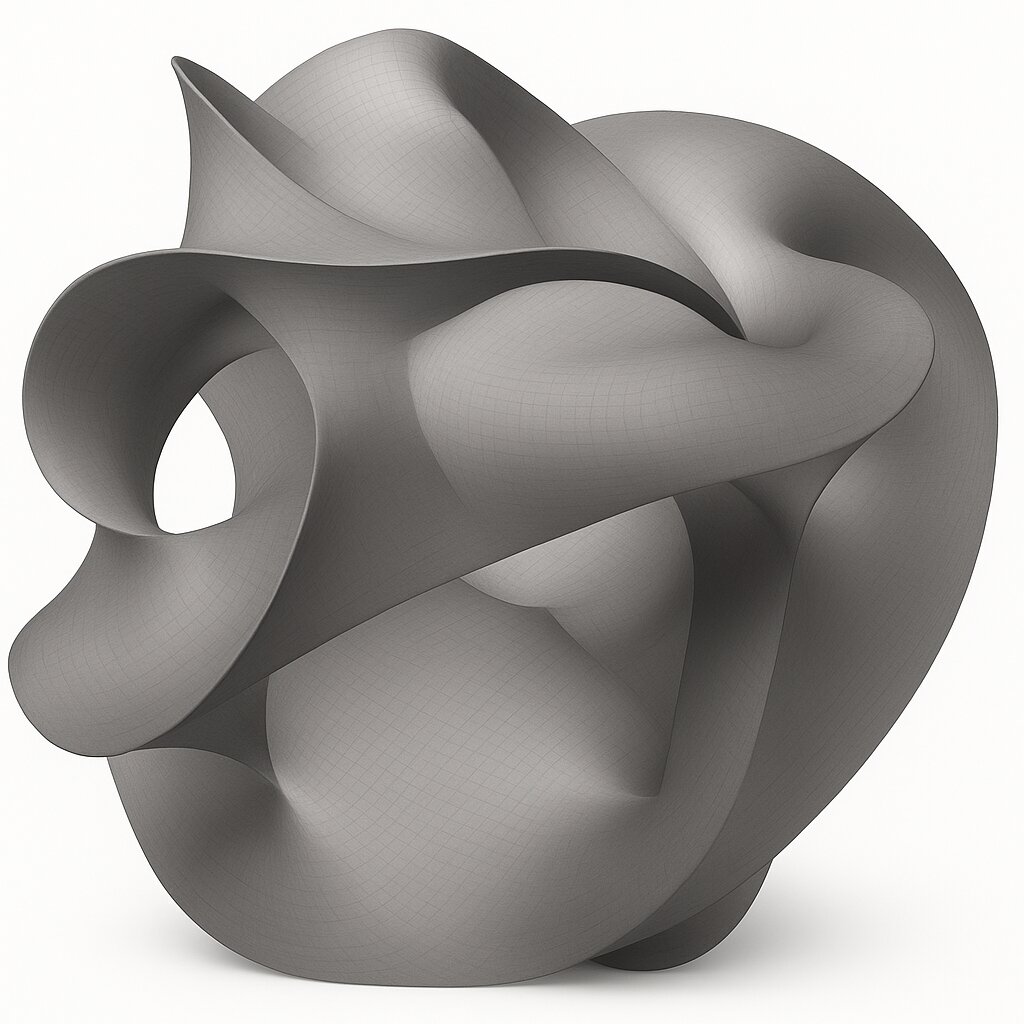

Visualization of a Calabi-Yau manifold’s shape, shown as a 2D projection of a 6-dimensional object. Such intricate surfaces are hypothesized to represent the compact extra dimensions in string theory. Despite their complex form, Calabi-Yau spaces are Ricci-flat, meaning they have no overall curvature - analogous to a perfectly flat sheet with no wrinkles or dents.

In simple terms, a Calabi-Yau manifold is defined by a set of special geometric and topological properties. Several key features distinguish Calabi-Yau manifolds from other shapes in mathematics:

-

Higher-Dimensional Shape: A Calabi-Yau manifold has more dimensions than the familiar three of everyday space. In the context of string theory, Calabi-Yau spaces typically come in six spatial dimensions, which, when added to our four-dimensional spacetime (three space + one time), make up a 10-dimensional universe as required by superstring theory.[12] (Mathematically, Calabi-Yau manifolds can exist in various dimensions; for example, a 6-dimensional Calabi-Yau refers to six real dimensions, or equivalently three complex dimensions.) These extra dimensions are not directly visible because they are curled up at extremely small scales.

-

Compactness: Calabi-Yau manifolds are compact, meaning they are finite in size and have no edges or boundaries (much like the surface of a sphere is finite yet without end). This compactness is crucial: it allows the extra dimensions to be “curled up” into tiny shapes that fit into each point in space. A classic analogy is to imagine a tiny circle attached at every point along a long line - the circle is small (compact) so from a distance the line still looks one-dimensional. In the case of Calabi-Yau manifolds, an entire six-dimensional shape is compactified at each point in our normal space, so that the extra dimensions are hidden from everyday observation.

-

Ricci-Flatness: One of the defining traits of a Calabi-Yau space is that it is Ricci-flat - in other words, it has no overall curvature associated with gravity. In Einstein’s general relativity, curvature (described by the Ricci tensor) is related to the presence of mass-energy. A Ricci-flat manifold is like a region of space with no matter causing curvature; it satisfies Einstein’s vacuum equations (like how outer space can be curved by stars, but a perfectly Ricci-flat space would be perfectly gravitationally neutral). To build intuition, imagine a perfectly stretched rubber sheet with no weights or distortions on it - it remains perfectly flat and tension-free. That is analogous to a Ricci-flat manifold: smooth and “flat” in a gravitational sense. This property is important because it means a Calabi-Yau can fit into a theory of gravity without introducing its own wrinkles; it’s a solution of Einstein’s equations in the absence of any mass or energy.

-

Complex Structure: Calabi-Yau manifolds are complex manifolds, which means locally they behave like spaces described by complex numbers (rather than just real numbers). In practical terms, having a complex structure endows the manifold with additional symmetry and mathematical richness. Each point in a Calabi-Yau space has coordinates that can be treated as pairs of real numbers (forming complex coordinates), which imposes a rigid structure on how the manifold can be deformed or measured. This is analogous to having a map that not only gives distances but also includes extra information (like landscape features or elevation) - the complex structure provides more “instructions” for the geometry. The complex structure also means Calabi-Yau manifolds belong to the class of Kähler manifolds,[10] implying they have a very “nice” geometric structure that allows calculus and algebraic geometry techniques to be used hand-in-hand. (One consequence is that Calabi-Yau spaces can also be described as algebraic varieties - essentially the solution sets to polynomial equations - making them a central object in modern geometry.)

-

Special Holonomy (SU(n) Holonomy): Perhaps the most technically subtle property, Calabi-Yau manifolds have a special holonomy group, specifically an holonomy in real dimensions (for example in six dimensions). Holonomy describes how the orientation of a vector (or a more abstract object like a spinor) is changed after moving around a closed loop on the manifold. A special holonomy means that after traversing any loop in a Calabi-Yau space, certain vectors return to their original orientation, indicating a high degree of symmetry in the space’s “twistiness”. An everyday analogy is traveling around the Earth: if you start at the equator with a pointing arrow and carry it all the way around the globe, you might find it rotated when you return to your starting point due to Earth’s curvature. In a Calabi-Yau manifold, despite its complex shape, there exists a way of orienting certain objects so that going around loops doesn’t change them - a sign of special, restrictive symmetry. This special holonomy is intimately connected to the manifold’s Ricci-flatness and complex structure. In physics terms, holonomy in a six-dimensional Calabi-Yau ensures the preservation of certain supersymmetries (quantum symmetries relating bosons and fermions) when the manifold is used as an extra-dimensional shape.[11] In fact, one reason Calabi-Yau spaces are used in string theory is that their special holonomy guarantees that some of the original symmetries of the higher-dimensional theory (like supersymmetry) remain unbroken after compactification.[13] This makes the resulting four-dimensional physics much more realistic.

These properties collectively define what a Calabi-Yau manifold is. In mathematical language, Yau’s theorem proved that if a space has the right topological conditions (essentially, the “trivial canonical bundle” or vanishing first Chern class), then it admits a Ricci-flat metric - fulfilling the Calabi-Yau criteria. The existence of a special holonomy () is another way to characterize a Calabi-Yau space. But from a conceptual standpoint, one can think of Calabi-Yau manifolds as “compact, curved-but-overall-flat” shapes with a high degree of internal symmetry. They often have intricate topology - for instance, they can have multiple “holes” or handles in higher-dimensional analogues (somewhat like a multidimensional donut with several holes), and it is precisely this rich topology that allows them to affect physics in interesting ways.

It should be noted that Calabi-Yau manifolds are not unique - in fact, there is an enormous variety of possible Calabi-Yau shapes (with different numbers of holes, different geometric details, etc.). Estimates suggest astronomically many distinct Calabi-Yau three-dimensional manifolds, on the order of tens of thousands or more, are possible even within certain classifications.[4] This plethora of options gives rise to what is whimsically called the “string theory landscape,”[14] a vast collection of possible universes each corresponding to a different choice of Calabi-Yau manifold and associated physical parameters. While this richness is mathematically fascinating, it also presents a challenge: not knowing which Calabi-Yau (if any) corresponds to our universe makes it hard to derive sharp predictions from string theory. Nonetheless, the general picture remains that if string theory is a valid description of nature, then Calabi-Yau manifolds (or something similar) are almost certainly the way nature hides those extra dimensions from view.

Implications for Unification and Theoretical Physics

Calabi-Yau manifolds sit at the crossroads of geometry and physics, and their study has had broad implications for the quest to unify nature’s forces. In string theory, which remains one of the leading paradigms for unification, Calabi-Yau shapes provide the means to include gravity (described by the shape of spacetime) and quantum field theory (described by vibrations of strings) in one coherent picture. By offering a way to reconcile the macroscopic world of gravity with the microscopic world of particle physics, Calabi-Yau manifolds contribute to the ongoing effort to formulate a single framework that encompasses all fundamental forces - a goal often dubbed the “Theory of Everything.” While this goal is not yet realized, the existence of Calabi-Yau solutions to the string equations is a concrete demonstration that such a unification is mathematically plausible: extra dimensions can be hidden and can influence particle physics in just the right way to give something like the universe we see.

Beyond string theory itself, Calabi-Yau manifolds have inspired new connections across disciplines. The impact on pure mathematics has been significant: string theorists’ interest in Calabi-Yau spaces led mathematicians to discover unexpected dualities (like mirror symmetry)[5][16] and to solve difficult problems in enumerative geometry by translating them into questions about physics.[17] Conversely, advances in mathematical understanding of Calabi-Yau spaces (for example, techniques to count their holes or classify their shapes) feed back into improved models for particle physics. This dialogue between math and physics exemplifies how progress in understanding the universe often requires a synergy of different fields.

In theoretical physics, Calabi-Yau manifolds have become a standard toolkit. Even proposals beyond the initial superstring models, such as brane-world scenarios or M-theory compactifications, often involve analogous geometric structures (in M-theory, for instance, one uses 7-dimensional spaces with holonomy, a concept analogous to Calabi-Yau’s holonomy).[6][15] The study of Calabi-Yau manifolds has thus broadened into the study of generalized manifolds with special holonomy and their physical implications. Each step forward in this area attempts to address open questions like: Why does our universe have the particles it does? Why are there three generations of matter? What picks out the specific forces and their strengths? Calabi-Yau compactification offers a framework in which such questions translate into concrete (if extremely complex) problems of geometry.

It’s important to emphasize that while Calabi-Yau manifolds provide a beautiful and logically consistent way to integrate extra dimensions into physics, experimental evidence is still lacking. No direct sign of extra dimensions or supersymmetry has been observed yet.[18] Nevertheless, Calabi-Yau manifolds have become deeply influential. They give theoretical physicists a rich playground to test ideas about unification, and they have driven home the lesson that the shape of extra dimensions can have real physical consequences. In that sense, Calabi-Yau geometry has shaped our thinking about what a unified theory could look like: not just a merge of forces, but a union of concepts from geometry, topology, and quantum physics.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Calabi-Yau manifolds are a foundation of modern attempts to unify gravity with the other fundamental forces. They encapsulate the idea that the universe might have more dimensions than meet the eye, and that the geometry of those unseen dimensions is crucial to the physics we observe. From their mathematical birth in the mid-20th century, through Yau’s definitive proof, to their role in cutting-edge string theory, Calabi-Yau manifolds illustrate how abstract geometry can become the fabric on which the laws of nature are written. The ongoing exploration of Calabi-Yau spaces continues to influence theoretical physics, offering both hope for a deeper understanding of the cosmos and new puzzles that spur scientific progress.[19] The journey of understanding Calabi-Yau manifolds is far from over, but it vividly demonstrates the power of thinking beyond visible dimensions and using pure mathematics to guide the search for fundamental truth.

References

- 1.Calabi, E. (1954). The space of Kähler metrics and the Calabi conjecture. Proceedings of the International Congress of Mathematicians, 1, 206-207. ↩

- 2.Yau, S. T. (1977). Calabi's conjecture and some new results in algebraic geometry. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 74(5), 1798-1799. ↩

- 3.Candelas, P., Horowitz, G. T., Strominger, A., & Witten, E. (1985). Vacuum configurations for superstrings. Nuclear Physics B, 258(1), 46-74. ↩

- 4.Kreuzer, M., & Skarke, H. (2002). Complete classification of reflexive polyhedra in four dimensions. Advances in Theoretical and Mathematical Physics, 4, 1209-1230. ↩

- 5.Greene, B. R., & Plesser, M. R. (1990). Duality in Calabi-Yau moduli space. Nuclear Physics B, 338(1), 15-37. ↩

- 6.Joyce, D. D. (2000). Compact manifolds with special holonomy. Oxford University Press. ↩

- 7.Yau, S. T. (2009). A survey of Calabi-Yau manifolds. In Surveys in Differential Geometry (Vol. 13, pp. 277-318). International Press. ↩

- 8.Aspinwall, P. S., Greene, B. R., & Morrison, D. R. (1993). Calabi-Yau moduli space, mirror manifolds and spacetime topology change in string theory. Nuclear Physics B, 416(2), 414-480. ↩

- 9.Douglas, M. R. (2003). The statistics of string/M theory vacua. Journal of High Energy Physics, 2003(05), 046. ↩

- 10.Huybrechts, D. (2005). Complex Geometry: An Introduction. Springer. ↩

- 11.Strominger, A. (1986). Superstrings with torsion. Nuclear Physics B, 274(2), 253-284. ↩

- 12.Green, M. B., Schwarz, J. H., & Witten, E. (1987). Superstring Theory (Vol. 1 & 2). Cambridge University Press. ↩

- 13.Polchinski, J. (1998). String theory (Vol. 2, Chapter 13). Cambridge University Press. ↩

- 14.Susskind, L. (2003). The anthropic landscape of string theory. arXiv preprint hep-th/0302219. ↩

- 15.Acharya, B. S., & Witten, E. (2001). Chiral fermions from manifolds of G2 holonomy. arXiv preprint hep-th/0109152. ↩

- 16.Hori, K., Katz, S., Klemm, A., Pandharipande, R., Thomas, R., Vafa, C., ... & Zaslow, E. (2003). Mirror symmetry (Vol. 1). American Mathematical Society. ↩

- 17.Cox, D. A., & Katz, S. (1999). Mirror symmetry and algebraic geometry (Vol. 68). American Mathematical Society. ↩

- 18.Dine, M. (2015). Supersymmetry and string theory: Beyond the standard model (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ↩

- 19.Becker, K., Becker, M., & Schwarz, J. H. (2007). String theory and M-theory: A modern introduction. Cambridge University Press. ↩