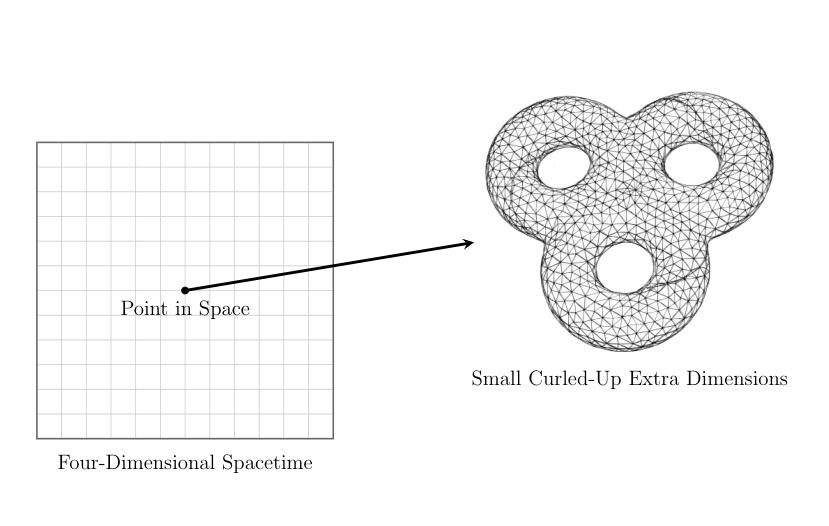

Our everyday experience is confined to a world with three spatial dimensions - length, width, and height - and one dimension of time. However, some of the most compelling and mathematically elegant theories in modern physics propose that the universe might possess more dimensions than we can directly perceive.[1] To reconcile these theoretical frameworks with the observed four-dimensional reality, physicists have developed the concept of compactification. Compactification, in this context, refers to a theoretical process where extra spatial dimensions are effectively “shrunk” or “rolled up” to incredibly small sizes, rendering them undetectable with our current observational capabilities.[2] This idea serves as a crucial link between the mathematical requirements of certain theories and the physical universe we experience.[3] If a theory posits the existence of additional dimensions, but our observations are limited to four, then a mechanism like compactification becomes necessary to explain the discrepancy.

Motivation for Higher Dimensions: Unifying the Fundamental Forces

The exploration of extra dimensions and their subsequent compactification is not merely a mathematical curiosity; it is deeply rooted in the quest to understand the fundamental nature of the universe and the forces that govern it. The Standard Model of particle physics, while remarkably successful in describing the electromagnetic, weak, and strong nuclear forces, has its limitations and does not include gravity. This incompleteness motivates the search for more fundamental theories that can provide a unified description of all the forces of nature.[3] Historically, the desire to unify seemingly disparate phenomena has driven significant progress in physics. For instance, James Clerk Maxwell’s work in the 19th century demonstrated that electricity and magnetism are, in fact, different manifestations of a single force, electromagnetism.

This historical precedent suggests that the four fundamental forces we currently recognize might also be unified under a more comprehensive framework. Some of the most promising candidates for such a unification, like string theory and M-theory, inherently require a specific number of dimensions for their mathematical consistency and to avoid internal contradictions.[4] String theory, for example, operates in ten spacetime dimensions, while M-theory requires eleven. The mathematical structure of these theories dictates these dimensional requirements, and compactification emerges as a way to align these theoretical necessities with the observed dimensionality of our universe.

At its core, compactification involves transforming spatial dimensions from being infinitely extended to being finite and incredibly small.[1] A helpful analogy for grasping this concept is that of a garden hose viewed from a distance. From afar, the hose appears to be a one-dimensional object, its length. However, upon closer inspection, a second dimension, its circumference, becomes apparent. If this circumference were extraordinarily small, an observer from a distance might only perceive the length, effectively overlooking the existence of the second, albeit compact, dimension.

Similarly, consider a two-dimensional surface, like a large carpet. If this carpet is rolled up tightly into a roll, it now appears to be a one-dimensional object. An ant living on the surface of the carpet could move in two dimensions when it was flat. Even when rolled up, the ant is still moving within those two dimensions, but one of those dimensions is now confined to the small circumference of the roll. This illustrates how a dimension can exist but be effectively hidden due to its compact nature. From a mathematical standpoint, a key characteristic of these compact dimensions is their periodicity. Traveling along a compact dimension will eventually lead back to the starting point, much like walking around a small circle. This “looping back” behavior distinguishes compact dimensions from the infinite, open dimensions we typically experience.

Historical Roots: Kaluza-Klein Theory and Early Compactification

The initial seeds of the idea of compactification were sown in the early 20th century by Theodor Kaluza and Oskar Klein, who were among the first to scientifically propose the existence of extra spatial dimensions.[5] In 1921, Kaluza took the groundbreaking step of extending Albert Einstein’s theory of general relativity, which describes gravity in four spacetime dimensions, to a five-dimensional framework (four spatial, one time). His remarkable achievement was demonstrating that within this five-dimensional theory, Einstein’s familiar four-dimensional theory of gravity and Maxwell’s theory of electromagnetism could both be contained. This suggested that these two fundamental forces might arise from a more fundamental geometric structure in a higher-dimensional spacetime.

In 1926, Oskar Klein built upon Kaluza’s work by proposing a physical explanation for why this extra spatial dimension was not observed.[6] Klein suggested that the extra dimension was curled up into a tiny circle, with a radius so small that it was beyond the reach of observation at the time. This concept of a “rolled-up” or “compactified” dimension provided a compelling reason for its apparent absence in our everyday experience. While the Kaluza-Klein theory offered an elegant unification of gravity and electromagnetism, it faced limitations in its ability to incorporate other fundamental forces and particles. Nevertheless, it represented a pivotal moment in theoretical physics, establishing the foundational idea that extra dimensions and their compactification could be key to understanding the universe’s fundamental forces.

The process by which a theory formulated in a higher number of dimensions manifests as a theory in a lower number of dimensions due to the compactification of the extra dimensions is known as dimensional reduction. When extra dimensions are compactified to extremely small sizes, the physical phenomena occurring within those dimensions become effectively invisible or averaged out at lower energy scales, resulting in an effective theory with fewer dimensions. The size of these compactified dimensions is crucial because it dictates the energy scale at which their effects might become noticeable.

If a dimension is compactified to an incredibly small scale, the energy required to probe it directly would be correspondingly high, potentially far beyond the reach of current experimental capabilities. In the context of dimensional reduction from a compactified dimension, an intriguing phenomenon arises: a single particle in the higher-dimensional theory can appear as a series of particles with different masses in the lower-dimensional theory. This occurs because the momentum of a particle along a compact dimension is quantized, meaning it can only take on discrete values. These different momentum states manifest as different mass states in the reduced-dimensional theory, a concept that could potentially explain the existence of multiple generations of elementary particles.

Compactification in String Theory: Calabi-Yau Manifolds and Orbifolds

Compactification plays a central role in modern theoretical frameworks like string theory and M-theory, which require ten and eleven spacetime dimensions, respectively, for their internal consistency.[4] To potentially describe our four-dimensional universe, these extra dimensions must be compactified. In these theories, the extra dimensions are not simply curled up randomly; they are compactified on specific, intricate geometric shapes known as manifolds.[7] The precise geometry of these compact manifolds is not arbitrary; it profoundly influences the properties of the resulting four-dimensional physics. Just as the shape of a musical instrument determines the sounds it can produce, the geometry of the compact dimensions dictates fundamental aspects of our universe.

A particularly important class of six-dimensional compact manifolds used in string theory compactifications are Calabi-Yau manifolds.[7] These complex geometric spaces possess specific mathematical properties that make them suitable for hosting the extra dimensions of string theory while preserving certain crucial symmetries. The vast number of possible Calabi-Yau manifolds leads to a multitude of potential ways to compactify string theory, each potentially resulting in a different four-dimensional universe with its own set of fundamental particles and forces. This concept is often referred to as the “string landscape.” Another type of space used for compactification is known as an orbifold. Orbifolds can be thought of as spaces obtained by taking a manifold and identifying points under a discrete symmetry group. They are often considered as singular limits of Calabi-Yau manifolds and provide another avenue for exploring the compactification of extra dimensions in string theory and related frameworks.

The geometry and topology of the compactified dimensions have profound implications for the physics we observe in our four-dimensional world. These features influence the fundamental properties of elementary particles, such as their mass and electric charge, and also determine the strengths of the fundamental forces that govern their interactions. Consider the analogy of a guitar string: its length and thickness (akin to the size and geometry of extra dimensions) dictate the frequencies (analogous to particle properties and force strengths) it can produce. Similarly, the intricate structure of the compact dimensions shapes the fundamental constants and particle spectra of our universe. Furthermore, the existence of multiple families of elementary particles, such as the electron, muon, and tau lepton, might be explained by the way fundamental particles can vibrate or move within these compactified dimensions. Different modes of vibration or motion within the hidden dimensions could manifest as distinct particles with different masses in our observable dimensions.

Experimental Constraints and Alternative Models for Extra Dimensions

The primary reason for assuming that any extra dimensions must be compact is the simple fact that we do not directly observe any large, extended extra spatial dimensions in our daily lives or through scientific experiments. If extra dimensions were as large as the three spatial dimensions we are familiar with, we would expect to be able to move freely along them and observe their effects directly. The absence of such observations strongly suggests that if extra dimensions exist, they must be hidden from us in some way. Compactification provides the most straightforward and mathematically consistent explanation for this concealment.

Moreover, experiments conducted at high-energy particle accelerators have placed increasingly stringent upper limits on the possible size of any extra dimensions.[8] These experimental constraints further support the idea that if extra dimensions exist, they must be incredibly small, possibly on the order of the Planck length (approximately 1.6 x 10^-35 meters). However, some theoretical models propose the possibility of larger extra dimensions, provided there is a mechanism that confines the particles of the Standard Model to a lower-dimensional subspace, often referred to as a “brane”.[2] In such scenarios, gravity, being a fundamental force of spacetime itself, might propagate in all dimensions, offering a potential way to indirectly detect these larger extra dimensions through subtle deviations from Newton’s law of gravity at very small distances.

Compactification is not merely a mathematical trick to hide unwanted dimensions; it is an integral part of the mechanism by which theories like string theory aim to achieve the long-sought-after unification of all fundamental forces.[9] String theory posits that the fundamental constituents of the universe are not point-like particles but rather tiny, vibrating strings. The different vibrational modes of these strings manifest as the various elementary particles we observe. The interactions between these strings, which are governed by the geometry of the higher-dimensional spacetime in which they propagate, give rise to the fundamental forces.

Compactification, by shaping the geometry of the extra dimensions, plays a crucial role in determining the specific spectrum of particles and the nature of their interactions in the resulting four-dimensional theory. M-theory, which aims to unify all consistent versions of superstring theory, also relies heavily on the concept of compactification. Different compactifications of M-theory on various types of manifolds can lead to different effective string theories in ten dimensions, highlighting the fundamental role of compactification in the interconnected web of these theoretical frameworks. Furthermore, the energy scales associated with the size of the compactified dimensions might be related to the energy scales at which Grand Unified Theories (GUTs) predict the strong, weak, and electromagnetic forces to merge into a single unified force. Thus, compactification offers a potential pathway towards realizing the unification of fundamental forces that has been a central goal of theoretical physics for over a century.

Conclusion

Compactification represents one of the most fascinating concepts in modern theoretical physics, bridging abstract mathematical theories with extra dimensions and our observable four-dimensional world. From its origins in the Kaluza-Klein theory of the 1920s to its central role in string theory and beyond, compactification has evolved into a sophisticated framework with profound implications for our understanding of fundamental physics.

The core idea-that extra dimensions might exist but remain hidden through compactification-has proven remarkably fruitful, spawning diverse theoretical approaches and offering potential solutions to long-standing problems in physics. These include the unification of fundamental forces, the hierarchy problem, and various aspects of particle phenomenology. Compactification provides a geometric perspective on many aspects of physics that are typically described through field-theoretic language, potentially offering deeper insights into the nature of reality.

Yet significant challenges remain. The stability of extra dimensions throughout cosmic history, the vast landscape of possible compactification schemes, and the difficulty of connecting theoretical predictions to experimental observations all present ongoing research problems. The resolution of these challenges will likely require not only advances in theoretical physics but also new experimental approaches and possibly conceptual breakthroughs in how we think about dimensions and physical law.

As research continues, compactification remains a vibrant field at the intersection of theoretical physics, mathematics, and cosmology. Whether or not extra dimensions ultimately prove to be a feature of our physical reality, the study of compactification has already enriched our understanding of the fundamental structure of theories and the deep connections between geometry and physics. It stands as a testament to the power of mathematical insight in guiding our exploration of the universe’s most profound mysteries.

References

- 1.Greene, B., 2010. The elegant universe: Superstrings, hidden dimensions, and the quest for the ultimate theory. WW Norton & Company. ↩

- 2.Randall, L. and Sundrum, R., 1999. Large mass hierarchy from a small extra dimension. Physical Review Letters, 83(17), p.3370. ↩

- 3.Polchinski, J., 1998. String theory: Volume 2, superstring theory and beyond. Cambridge University Press. ↩

- 4.Witten, E., 1995. String theory dynamics in various dimensions. Nuclear Physics B, 443(1-2), pp.85-126. ↩

- 5.Kaluza, T., 1921. Zum unitätsproblem der physik. Sitzungsberichte der Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin, pp.966-972. ↩

- 6.Klein, O., 1926. Quantentheorie und fünfdimensionale relativitätstheorie. Zeitschrift für Physik, 37(12), pp.895-906. ↩

- 7.Candelas, P., Horowitz, G.T., Strominger, A. and Witten, E., 1985. Vacuum configurations for superstrings. Nuclear Physics B, 258, pp.46-74. ↩

- 8.Arkani-Hamed, N., Dimopoulos, S. and Dvali, G., 1998. The hierarchy problem and new dimensions at a millimeter. Physics Letters B, 429(3-4), pp.263-272. ↩

- 9.Green, M.B. and Schwarz, J.H., 1984. Anomaly cancellations in supersymmetric D= 10 gauge theory and superstring theory. Physics Letters B, 149(1-3), pp.117-122. ↩