The Hubble constant, H₀, encapsulates the present-day expansion rate of the universe by linking a galaxy’s recession speed to its distance, the slope of the linear relation first identified by Hubble. Because redshift stretches a galaxy’s light as space expands, combining redshift with an independent distance estimate yields this slope and turns a qualitative expansion into a measurable rate. This single parameter functions as a cosmic clock: a higher value implies that expansion has been faster and the universe is younger, while a lower value implies more time for galaxies and structures to assemble. Because H₀ is tied to the Friedmann equations that govern cosmic dynamics, it also acts as a bridge between observations and the content of the universe, connecting measures of matter and dark energy to the overall expansion history and turning distance measurements into a test of the entire cosmological framework.

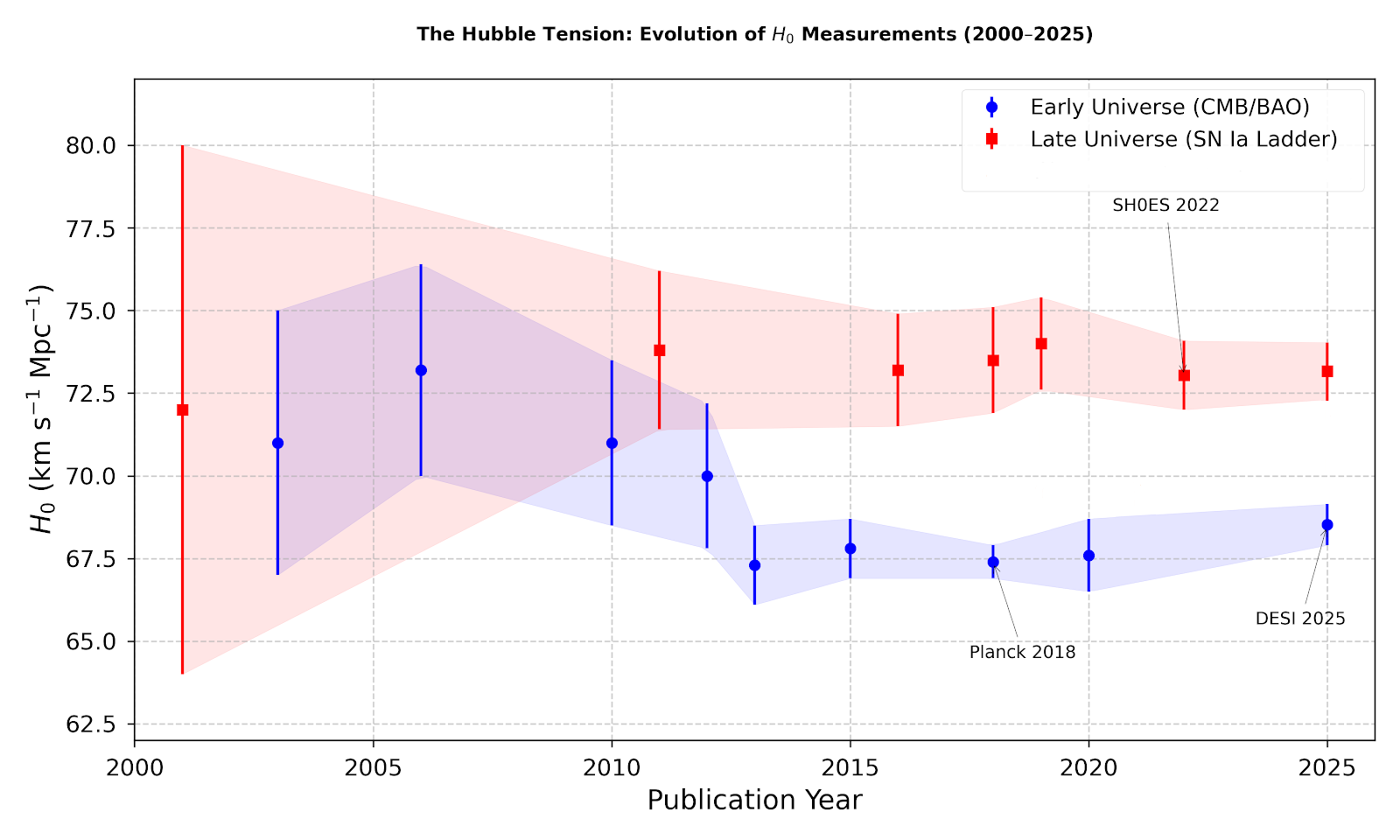

Over the last decade, cosmology has shifted from debating whether H₀ is closer to 50 or 100 to confronting an unexpected mismatch between two high‑precision approaches. Local measurements that rely on distance indicators in the nearby universe yield values around 70–76 km/s/Mpc, whereas inferences from the cosmic microwave background, interpreted through ΛCDM, sit near 67–68 km/s/Mpc. The gap is roughly nine percent, far larger than the quoted uncertainties, and is widely known as the Hubble tension, signifying a disagreement between late‑time and early‑time determinations that cannot be dismissed as statistical noise.[1] In statistical terms, the mismatch now reaches several standard deviations, which would be unlikely if both methods were simply fluctuating around the same true value.

Instead of converging as measurements improved, the discrepancy has become sharper. Hubble and JWST observations have strengthened the local distance ladder, while CMB analyses have continued to deliver remarkably stable results, leaving the two approaches locked in disagreement. NASA’s Webb team characterizes this as a persistent difference between expansion rates measured with distance indicators and those predicted from the Big Bang’s afterglow, underscoring that the tension has not faded with better data but has instead become an enduring problem for the standard cosmological model.[4] The consequence is that a parameter once thought to be almost settled now sits at the center of debates about the universe’s composition and history.

Local Measurements and the Cosmic Distance Ladder

The distance‑ladder approach builds from the bottom up, using geometry to fix the brightness of nearby stars and then extending those calibrations to ever larger scales. Parallax measurements of nearby stars set the absolute luminosity of Cepheid variables, whose pulsation periods serve as reliable indicators of intrinsic brightness; those Cepheids are observed in nearby galaxies to establish their distances, and Type Ia supernovae then carry the scale out to hundreds of megaparsecs. The Hubble Space Telescope Key Project spent years applying this ladder to dozens of galaxies and, by 1999, reported an H₀ near 70 km/s/Mpc with about a ten percent uncertainty, demonstrating that careful calibration could overcome decades of disagreement about the expansion rate.[2] That achievement established a robust local scale against which later measurements could be compared.

Recent work has focused on reducing every source of uncertainty in this ladder, including improved parallax baselines, infrared observations that minimize dust extinction, and larger samples of Cepheids and supernovae that reduce statistical scatter. The SH0ES collaboration and related teams have combined Hubble and JWST observations to refine the calibration of these standard candles, achieving percent‑level precision and repeatedly finding H₀ values near 73–74 km/s/Mpc. NASA’s analysis of new Hubble data emphasizes that this refined local measurement implies an expansion rate about nine percent faster than that inferred from early‑universe modeling, highlighting how stable the local value has become despite intense scrutiny.[3] The central result is not a single number but the repeated confirmation of that number across increasingly precise datasets.

The ladder’s power lies in its redundancy, but its vulnerabilities also stem from the fact that each rung depends on careful astrophysical modeling. Cepheid luminosities can be affected by metallicity, crowding in galactic disks, and interstellar dust, while Type Ia supernovae can vary with their host‑galaxy environment or subtle evolutionary effects; even small biases at each rung can cumulatively shift H₀. For this reason, astronomers routinely cross‑check the ladder against alternative anchors such as the tip of the red‑giant branch, megamaser distances, or surface‑brightness fluctuations, not to replace Cepheids and supernovae but to test whether hidden systematics could push the local value upward or downward. The ladder therefore remains both a triumph of observational ingenuity and a focus of intense calibration work.

Early‑Universe Inference from the CMB and ΛCDM

The early‑universe method begins with the cosmic microwave background, the faint afterglow from the epoch when the universe cooled enough for atoms to form, leaving a snapshot of primordial density ripples. Those tiny temperature fluctuations encode a characteristic sound horizon scale that acts as a standard ruler, and fitting the angular pattern of peaks with the ΛCDM model allows the current expansion rate to be inferred with extraordinary precision. Planck’s measurements of the CMB, combined with the standard model’s assumptions about matter and dark energy, yield a present‑day H₀ of about 67.4 km/s/Mpc, with uncertainties far below one percent.[5] The result is sometimes described as a prediction because it extrapolates a physics‑rich early snapshot into the present.

This inference is exceptionally precise but intrinsically model‑dependent, because it relies on the assumption that the physics governing the early universe is fully captured by ΛCDM’s ingredients and that the universe has evolved smoothly to the present. The CMB does not measure H₀ directly; it measures the early‑time parameters and then extrapolates using the Friedmann equations, so any change to the dark‑energy behavior, the relativistic particle content, or the geometry of space would alter the predicted H₀ even if the CMB data themselves remain unchanged. The strength of the approach lies in its internal consistency across multiple parameters, but the tension arises precisely because this internally consistent early‑time prediction does not match the direct late‑time measurements.

Independent and Emerging Probes

Gravitational‑wave standard sirens offer a direct, ladder‑free way to measure cosmic expansion by using the waveform amplitude of compact‑binary mergers as a distance indicator. The gravitational‑wave signal encodes the absolute luminosity distance, and if the host galaxy is identified, its redshift provides the recession speed needed to compute H₀, avoiding Cepheid or supernova calibrations altogether. The first such event, GW170817, produced a broad estimate consistent with both the local and CMB values but with uncertainties still too large to arbitrate the tension. As detectors gain sensitivity and the number of events increases, standard sirens are expected to provide an independent yardstick that is conceptually cleaner than the distance ladder yet rooted in an entirely different physical regime.

Other independent probes are also maturing, including strong‑lensing time delays that measure distances through the light‑travel‑time differences in lensed quasars, megamaser galaxies whose geometric disks provide precise distances, surface‑brightness fluctuations in early‑type galaxies, and baryon acoustic oscillation measurements combined with supernova data to map the expansion at intermediate redshifts. Each of these methods has its own systematics and assumptions, but their value lies in offering cross‑checks that do not depend on Cepheid calibrations or the CMB’s early‑time physics. Over the next decade, the convergence or divergence of these alternative probes will play a key role in deciding whether the tension is a matter of calibration or a sign of missing physics.

Historical Milestones

The current tension stands in contrast to a long history of uncertainty about the expansion rate. After Hubble’s 1929 discovery, astronomers argued for decades about whether the universe was expanding quickly or slowly, with Allan Sandage favoring values near 50 km/s/Mpc and Gérard de Vaucouleurs arguing for values near 100. The debate was not merely academic; it reflected deep disagreements about distance indicators and even became personal, illustrating how uncertain the cosmic distance scale once was and how strongly scientists defended their methodologies.[6] That contentious history underscores how far the field has moved toward precision.

The launch of the Hubble Space Telescope and the development of larger detectors gradually transformed that controversy into a more disciplined, data‑rich endeavor. By the late 1990s and early 2000s, the distance ladder could be calibrated beyond the Local Group, giving cosmologists a reliable baseline for expansion measurements and allowing the field to talk in terms of percent‑level uncertainties rather than factors of two. At the same time, a coherent picture of a universe dominated by dark energy and dark matter emerged, and the idea of precision cosmology took hold as both observations and theory converged on a consistent framework for interpreting expansion data.

In the 2000s and 2010s, CMB missions such as WMAP and Planck delivered exquisite measurements of the early universe, while local programs refined Cepheid and supernova calibrations to ever higher precision. The surprise was that the two approaches did not converge as expected; instead, as uncertainties tightened, the mismatch crystallized into a statistically significant difference. The Hubble tension thus emerged not from a lack of data but from an abundance of precise data that refused to agree, turning a former measurement dispute into a potential challenge to the standard cosmological model.

Interpreting the Mismatch

With the discrepancy now at the level of several standard deviations, the community has largely framed the problem as a choice between two broad explanations: unrecognized systematic errors in one or both measurement approaches, or new physics that changes the expansion history between the early universe and today. Both possibilities are plausible in principle, yet each faces stringent tests. Systematics would need to bias measurements by several percent despite extensive calibration work, while new physics would need to preserve the success of ΛCDM on most other observations while altering only the inferred H₀. This duality has driven a parallel effort of measurement audits and theoretical innovation.

On the measurement side, attention focuses on the subtle astrophysical effects that can influence standard candles and standard rulers. Cepheid luminosities may vary with metallicity, dust, or crowding, and the calibration of Type Ia supernovae can depend on host‑galaxy environments or selection effects; even small biases at each rung can cumulatively shift H₀. Recent JWST analyses that rely on alternative distance indicators such as the tip of the red‑giant branch have yielded values closer to the CMB prediction, contrasting with past Hubble‑based measurements in the low 70s and leaving open the possibility that the tension could be reduced within the local measurements themselves.[5] This does not resolve the issue, but it highlights how sensitive H₀ is to the choice of calibration anchors.

On the theory side, researchers have proposed modifications that change the early‑universe expansion rate and thus the sound horizon scale inferred from the CMB. Two widely discussed ideas are early dark energy, in which dark energy briefly contributed more to the energy budget before recombination, and dark radiation, in which extra relativistic particles alter the expansion rate and the acoustic peak structure. NASA’s discussion of the tension notes these possibilities explicitly, emphasizing that either additional early‑time energy or new light particles could reconcile the CMB‑based prediction with a higher local H₀, though both ideas remain speculative and tightly constrained by other datasets.[3] Any successful model must therefore thread a narrow path between alleviating the tension and preserving the broader successes of ΛCDM.

Commentators have therefore urged caution about declaring a cosmological revolution too quickly, noting that the tension could signal missing physics but might also reflect unresolved internal differences among late‑time indicators. Quanta Magazine captures this ambivalence by noting that the discrepancy suggests something may be missing from the theoretical model while also highlighting the possibility that the conflict could be within the star‑based measurements themselves, reinforcing the need for multiple cross‑checks before any definitive claim about new physics is made.[8] In this sense, the debate has become a test of both observational methodology and theoretical flexibility.

Implications and Future Directions

Because H₀ anchors the cosmic timeline, the tension has broad consequences. A value near 67 implies an age of roughly 13.8 billion years, while a value near 74 shortens that to around 12.9 billion years, potentially affecting models of early galaxy formation and the growth of large‑scale structure; it also intersects with other cosmological tensions such as discrepancies in the clustering amplitude of matter. If the discrepancy is real and not due to measurement bias, resolving it would require a significant revision to the standard cosmological model, a possibility that underscores why some commentators argue that the issue could demand a drastic shift in how scientists understand the universe.[7] The tension therefore acts as a lever on a wide range of cosmological inferences, not just on a single parameter.

The path forward is therefore as much observational as theoretical. Continued JWST observations, improved Gaia parallaxes, and larger time‑domain surveys from the Vera Rubin Observatory will refine the local distance ladder, while CMB experiments and large‑scale structure surveys such as Euclid and the Roman Space Telescope will sharpen early‑universe constraints. Meanwhile, the accumulation of gravitational‑wave standard sirens and improved strong‑lensing analyses will provide independent checks with very different systematics, and the combination of these methods should reveal whether the discrepancy is a calibration artifact or a signpost of new physics. The next decade is likely to be decisive, either dissolving the tension or converting it into a durable anomaly that forces theory to adapt.

Conclusion

The Hubble tension has evolved from a technical measurement problem into a potential stress test of the standard cosmological model. Local distance ladders built from Cepheids and supernovae have become extraordinarily precise, while CMB‑based inferences remain internally consistent and equally precise, leaving a gap that resists easy reconciliation. The most plausible outcomes are either a subtle but consequential systematic error hidden in one of the methods or a new piece of physics that modifies the universe’s early expansion without spoiling its many successes. In either scenario, the tension illustrates how precision can sharpen rather than resolve scientific questions.

Whether the discrepancy ultimately fades with improved calibration or persists as a genuine sign of new physics, it will shape cosmology’s next stage. The ongoing dialogue between late‑time and early‑time measurements is already driving methodological innovation, from refined stellar calibrations to gravitational‑wave distance measurements, and it underscores the value of independent approaches to fundamental parameters. For now, H₀ remains the parameter that links the universe’s past to its present and future, and the task of reconciling its measurements stands as one of the most consequential challenges in modern astrophysics.

References

- 1.science.nasa.gov Hubble Constant and Tension. https://science.nasa.gov/mission/hubble/science/science-behind-the-discoveries/hubble-constant-and-tension/ ↩

- 2.science.nasa.gov Hubble Completes Eight-Year Effort to Measure Expanding Universe. https://science.nasa.gov/missions/hubble/hubble-completes-eight-year-effort-to-measure-expanding-universe/ ↩

- 3.science.nasa.gov Mystery of the Universe's Expansion Rate Widens with New Hubble Data. https://science.nasa.gov/missions/hubble/mystery-of-the-universes-expansion-rate-widens-with-new-hubble-data ↩

- 4.science.nasa.gov (2023). Webb Confirms Accuracy of Universe’s Expansion Rate Measured by Hubble, Deepens Mystery of Hubble Constant Tension. https://science.nasa.gov/blogs/webb/2023/09/12/webb-confirms-accuracy-of-universes-expansion-rate-measured-by-hubble-deepens-mystery-of-hubble-constant-tension/ ↩

- 5.news.uchicago.edu New Webb Telescope Data Suggests Our Model Universe May Hold After All. https://news.uchicago.edu/story/new-webb-telescope-data-suggests-our-model-universe-may-hold-after-all ↩

- 6.www.astronomy.com Tension at the Heart of Cosmology. https://www.astronomy.com/science/tension-at-the-heart-of-cosmology/ ↩

- 7.www.sciencenews.org Cosmology Expansion Universe. https://www.sciencenews.org/article/cosmology-expansion-universe ↩

- 8.www.quantamagazine.org (2024). The Webb Telescope Further Deepens the Biggest Controversy in Cosmology. https://www.quantamagazine.org/the-webb-telescope-further-deepens-the-biggest-controversy-in-cosmology-20240813/ ↩