Astronomers have long considered the possibility of additional, yet undiscovered planets in the solar system. The discovery of Neptune in 1846, based on mathematical predictions, demonstrated the potential for identifying new planets through indirect evidence. In recent years, some researchers have proposed the existence of a ninth planet, referred to as Planet 9, to explain certain orbital patterns observed in the outer solar system.[2] This report outlines the development of the Planet 9 hypothesis, examining the key observations that have contributed to this idea and assessing the current state of the supporting evidence.

Historical Context

The story of Planet 9 begins not with direct observation but with the detection of unusual orbital patterns among distant objects located beyond Neptune. These initial signs emerged from meticulous studies of the Kuiper Belt, a vast ring of icy bodies extending past Neptune’s orbit. The Kuiper Belt, which includes thousands of small celestial bodies such as Pluto and other dwarf planets, offers crucial insights into the structure and history of the outer solar system. Detailed analyses of Trans-Neptunian Objects (TNOs)-bodies orbiting the Sun at average distances greater than Neptune-laid the foundation for the Planet 9 hypothesis. Astronomers observed peculiar alignments among the most distant TNOs, whose orbital orientations differed significantly from random distribution. This unusual alignment was particularly evident in the “argument of perihelion,” which describes the orientation of an object’s closest approach to the Sun. Rather than appearing randomly dispersed, these points clustered noticeably, implying an unseen gravitational force shaping their orbits.

This observed orbital clustering was highly significant, as the statistical likelihood of such alignment occurring by chance alone was exceedingly low-approximately 0.007%. This improbability strongly suggested a dynamical explanation rather than mere coincidence, indicating the presence of an influential celestial body. Consequently, the formal introduction of the Planet 9 hypothesis occurred in January 2016 through the work of astronomers Konstantin Batygin and Michael Brown, who published their influential paper “Evidence for a Distant Giant Planet in the Solar System” in The Astronomical Journal.[2] Their research demonstrated that the observed clustering extended beyond orbital orientations to physical space, with tightly confined perihelion positions and orbital planes. They proposed a distant, eccentric planet with a mass exceeding roughly ten Earth masses as the gravitational entity responsible for maintaining these orbital alignments. According to their calculations, this hypothetical Planet 9 would orbit within the same plane as these distant Kuiper Belt objects, but with its perihelion positioned 180 degrees opposite, ensuring gravitational interactions that sustain the observed orbital patterns over extensive periods.

Expanding Evidence and Alternative Perspectives

Following the initial proposal, researchers expanded their investigations to determine whether additional anomalies in the outer solar system could also be explained by the Planet 9 hypothesis. This approach significantly broadened the supporting evidence base for the existence of this distant planet. Further studies demonstrated that Planet 9 could account for another intriguing characteristic of the outer solar system: the presence of highly inclined, and sometimes retrograde, trans-Neptunian objects. These objects orbit the Sun at substantial angles relative to the primary planetary plane, with some even traveling in the opposite direction to the major planets. Numerical simulations indicated that a distant, Neptune-like planet on an eccentric and mildly inclined orbit could explain these anomalies.[3] This insight provided clarity regarding peculiar Kuiper Belt members such as “Drac” and “Niku,” which previously eluded explanation within traditional solar system models. Consequently, this additional evidence bolstered the Planet 9 hypothesis by highlighting its broad explanatory capability-offering a unified mechanism for diverse irregularities observed in the outer solar system.

More recent research continues to strengthen the argument for Planet 9. In April 2024, a significant study examined low-inclination, Neptune-crossing TNOs, further validating the hypothesis.[1] These objects, whose paths intersect with Neptune’s orbit, displayed orbital configurations remarkably consistent with predictions derived from models incorporating Planet 9. Through extensive computer simulations accounting for gravitational influences from giant planets, the Galactic tide, and nearby passing stars, researchers determined that observational data strongly supported the existence of Planet 9. Specifically, statistical analysis robustly rejected scenarios excluding Planet 9, achieving a confidence level near 5 sigma-a threshold comparable to discovery standards in particle physics. This study not only reinforced the Planet 9 hypothesis but also provided specific observational predictions, offering clear directions for future research as observational capabilities continue to advance.

Theorized Characteristics

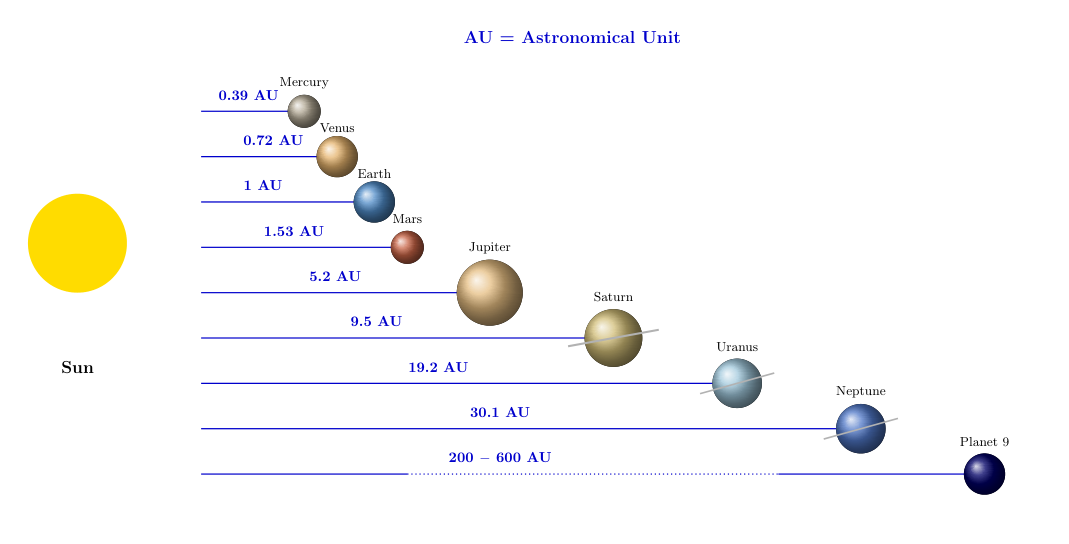

Planet 9 is hypothesized to be a substantial world with physical and orbital properties quite different from the eight confirmed planets in our solar system. Current models suggest Planet 9 has a mass between approximately 5-10 Earth masses, placing it in the super-Earth category-larger than our planet but smaller than the ice giants Uranus and Neptune.[2] Some more recent models suggest it could be somewhat less massive, perhaps 1.5-3 Earth masses, though still significant enough to influence distant objects. The orbit of Planet 9 is theorized to be extremely distant from the Sun, with a semimajor axis (average orbital distance) estimated between 250-500 astronomical units (AU). For perspective, Earth orbits at 1 AU, while Neptune, the most distant known planet, orbits at approximately 30 AU. This places Planet 9 at least eight times farther from the Sun than Neptune, explaining why it has eluded detection thus far. The planet’s closest approach to the Sun (perihelion) is estimated at around 200 AU, while its most distant point (aphelion) could reach significantly farther.

Unlike the major planets whose orbits lie roughly in the same plane, Planet 9’s orbit is thought to be substantially inclined, tilted at approximately 30 degrees relative to the ecliptic plane. This inclined orbit may explain some of the unusual orbital characteristics observed in distant Kuiper Belt objects.[3] Additionally, the orbit is likely highly eccentric (elongated rather than circular), which would cause the planet’s distance from the Sun to vary considerably throughout its orbital period. At these extreme distances, Planet 9 would receive very little solar radiation, making it an extraordinarily cold world with a surface temperature likely only a few degrees above absolute zero. Current detection searches explore distances ranging from 300 AU to as far as 2000 AU, highlighting the vast region where this object might be located. Specific models have placed it at approximately 460 AU, though this remains uncertain without direct observation.

The primary evidence for Planet 9’s existence comes not from direct observation but from its gravitational influence on smaller bodies in the outer solar system. The Kuiper Belt, a region beyond Neptune populated by icy bodies, shows several anomalous features that appear to be best explained by the presence of a massive, distant planet. One of the most compelling pieces of evidence is the clustering of orbits among distant Trans-Neptunian Objects (TNOs). Several TNOs with semimajor axes greater than 250 AU show statistically significant clustering in their orbital parameters, suggesting an unseen influence.[2] Planet 9’s gravitational pull appears to explain three fundamental properties observed in the distant Kuiper Belt: the existence of “detached objects” that remain unaffected by Neptune’s gravity, a significant population of high-inclination objects, and extreme orbits of certain bodies like Sedna. Additionally, deviations in the mean plane of the Kuiper Belt at distances beyond 100 AU align with models incorporating Planet 9. Its gravitational effects also appear consistent with the presence of stable TNOs in various Neptunian mean motion resonances, further supporting the possibility that this hypothetical planet exists.

Methods to Detect Planet 9

Finding Planet 9 poses a significant challenge due to its presumed large distance, relatively small size compared to giant planets, and the extensive region of sky that must be surveyed. Despite these challenges, several innovative methods are currently in use. Millimeter-wavelength observations with instruments such as the Atacama Cosmology Telescope (ACT) (now decommissioned in favor of Simons Observatory) in Chile represent one such approach.[4] Researchers conducted a blind shift-and-stack analysis using ACT data collected at frequencies of 98 GHz (2015-2019), 150 GHz (2013-2019), and 229 GHz (2017-2019). This technique involves combining multiple observational images, shifting them according to hypothetical orbital paths, and searching for consistent signals. Although this effort has yet to yield definitive detections, it has significantly constrained Planet 9’s potential millimeter-wave emissions across extensive orbital parameters.

Additionally, planetary exploration missions offer promising avenues for indirect detection. The proposed Uranus Orbiter and Probe mission could measure gravitational influences precisely enough to estimate Planet 9’s location and mass through detailed trajectory analysis during its interplanetary journey. Using advanced Monte Carlo Markov chain simulations, scientists anticipate localizing Planet 9 within approximately 0.2 square degrees, assuming a mass of about 6.3 Earth masses at 460 AU.[1] Enhanced precision in measurement could further narrow this uncertainty dramatically. Citizen science initiatives, such as Backyard Worlds: Planet 9, have also proven beneficial by engaging public volunteers in analyzing extensive astronomical data, although to date these have primarily led to discoveries of other distant objects like brown dwarfs. Due to Planet 9’s expected faintness, innovative and sensitive detection methodologies remain critical to distinguishing the planet from surrounding celestial backgrounds.

Alternative Hypotheses

While the gravitational influence of a distant planet continues to be the primary explanation for observed orbital anomalies in the outer solar system, alternative hypotheses regarding the nature of “Planet 9” have also been explored. In 2023, researchers proposed that instead of a conventional planet, Planet 9 could potentially be an “axion star”-a gravitationally bound cluster composed of theoretical particles known as axions or axion-like particles. Such an axion star, with a mass approximately equal to five Earth masses, would exhibit gravitational behavior similar to that expected from Planet 9. Moreover, the likelihood of the solar system capturing an axion star was estimated to be comparable to or even greater than capturing a free-floating planet under specific conditions. This concept broadens the theoretical framework beyond traditional rocky or gaseous planetary bodies.

In 2019, physicists Jakub Scholtz and James Unwin proposed that Planet Nine could be a primordial black hole (PBH) with a mass comparable to a planet, estimated around 5-10 Earth masses (Scholtz & Unwin, 2019), implying a Schwarzschild radius on the order of just a few centimeters-roughly akin to the diameter of a golf ball-for such a compact object.[5] The possibility that Planet Nine might be a PBH has also been discussed in broader contexts, given observational similarities between these two exotic objects. Primordial black holes, formed shortly after the Big Bang, would be incredibly compact and challenging to detect, distinguishable primarily by gravitational effects rather than reflective properties. If this hypothesis proves accurate, the implications would be significant: PBHs of planetary mass could naturally explain gravitational anomalies attributed to Planet Nine and potentially offer a direct observational handle on dark matter.

Despite this intriguing potential, primordial black holes of several Earth masses would be exceedingly difficult to detect. They might be identified through gravitational microlensing-where a PBH briefly magnifies the light from distant stars-or by spotting faint Hawking radiation emissions.[5] However, current observational capabilities are insufficient to detect such low-energy signals, rendering the PBH scenario speculative. Moreover, cosmological models suggest that primordial black holes in this mass range are exceedingly rare, further challenging their plausibility. Existing and upcoming instruments-such as the Vera C. Rubin Observatory, ESA’s Euclid telescope, and the microlensing surveys conducted by missions like Gaia-may help test this hypothesis, but at present, observational data neither conclusively supports nor rules it out.

Conclusion

The Planet 9 hypothesis represents a significant development in the study of the solar system. Since its formal introduction in 2016, multiple lines of evidence derived from trans-Neptunian objects have accumulated, suggesting the possible presence of a large, distant planetary body. The unusual orbital patterns observed in the outer solar system indicate that a substantial mass-potentially a planet of approximately 10 Earth masses-may exist beyond Neptune. These deviations in orbital dynamics remain difficult to explain without invoking an external gravitational influence, strengthening the case for the Planet 9 hypothesis.

While direct observation remains the definitive test of this hypothesis, indirect evidence has continued to grow. Each new study examining different populations of distant objects adds to the body of knowledge, with recent analyses challenging Planet 9-free models with high statistical confidence. Whether future observations confirm the existence of a conventional planet, reveal an alternative explanation such as an exotic astrophysical object, or suggest an entirely new mechanism, the search for Planet 9 continues to drive advances in astronomical research. As observational capabilities improve, direct detection may become possible, offering new insights into the structure and evolution of the outer solar system.

References

- 1.Batygin, K., Morbidelli, A., Brown, M. E. & Nesvorny, D. (2024) Generation of Low-Inclination, Neptune-Crossing TNOs by Planet Nine. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.11594. ↩

- 2.Batygin, K. and Brown, M.E., 2016. Evidence for a distant giant planet in the solar system. The Astronomical Journal, 151(2), p.22. ↩

- 3.Gomes, R., Deienno, R. and Morbidelli, A., 2016. The inclination of the planetary system relative to the solar equator may be explained by the presence of planet 9. The Astronomical Journal, 153(1), p.27. ↩

- 4.Naess, S., Aiola, S., Battaglia, N., Bond, R.J., Calabrese, E., Choi, S.K., Cothard, N.F., Halpern, M., Hill, J.C., Koopman, B.J. and Devlin, M., 2021. The atacama cosmology telescope: A search for planet 9. The Astrophysical Journal, 923(2), p.224. ↩

- 5.Scholtz, J. and Unwin, J., 2020. What if planet 9 is a primordial black hole?. Physical Review Letters, 125(5), p.051103. ↩