The Quantum eraser experiment has sparked some controversy. Sabine Hossfelder addresses it in her YouTube video “The Delayed Choice Quantum Eraser, Debunked,” while Sean Carroll offers insights in his blog post “The Notorious Delayed-Choice Quantum Eraser”. Both agree that there is no mystical retrocausality involved, and in that regard, it can be considered debunked. However, I think it remains an interesting experiment, and I would like to share an analysis with you.

Introduction and Wheeler’s Delayed Choice

The delayed-choice experiment was first conceived as a thought experiment by physicist John Archibald Wheeler in the late 1970s.[7] Wheeler wanted to ask: when does a quantum particle decide to behave like a wave or a particle? In the classic double-slit experiment, if one measures interference, one might naively think the particle “went through both slits as a wave,” and if one measures which slit, one might think it “went through one slit as a particle.”[9] Wheeler proposed arranging an experiment where the decision to observe an interference pattern or to determine the particle’s path is made after the particle has entered (or even passed through) the double-slit apparatus. In one famous scenario, Wheeler imagined using distant cosmic light: light from a quasar bent by a gravitational lens could reach Earth by two paths (like the two “slits”).[7] One could choose at the last moment to either place detectors to see which path the quasar photon took, or instead let the two paths recombine to observe interference. Remarkably, even if that choice is made billions of years after the photon left the quasar, the outcome still conforms to the choice - interference if and only if both paths are indistinguishable. This seems as if the photon “knew” what experiment was coming and adjusted its behavior accordingly, thus striking at our common-sense notions of causality. Wheeler’s provocative phrasing was that it is “wrong… to think of the past as already existing in all detail; the past has no existence except as it is recorded in the present”, meaning that how we choose to observe a quantum event can seemingly influence how we regard its past behavior. The motivation was to illustrate the central point of quantum theory: you cannot assume a photon has a definite classical history (wave or particle) independent of how you observe it. Any satisfactory interpretation of quantum mechanics must deal with this weird feature without allowing actual contradictions.

For years, Wheeler’s delayed-choice remained a thought experiment, since it required ultra-fast changes in the apparatus or clever timing. By the 1980s, however, technology caught up. In 1984, for instance, scientists demonstrated delayed-choice behavior in laboratory interferometers,[10] confirming that inserting or removing a final beam-splitter at the last moment changed whether interference was seen, without any paradox (the particle didn’t retroactively change an already observed outcome; rather, the outcome wasn’t determined until the final moment). These experiments supported Wheeler’s assertion that what we do at the exit port (the final measurement setup) determines whether the photon shows wave-like or particle-like behavior.

A simplified version of Wheeler’s experiment involves a 50:50 beam splitter.[11] When a photon encounters this device, there is an equal chance for it to take one of two paths-let’s call them Path A and Path B. If we place a detector on each path, we only see a single detector click, giving the impression that the photon chose one route like a little billiard ball (a particle). On the other hand, if we do not place detectors right away but instead recombine the two possible paths using a second beam splitter, the photon seems to produce an interference effect. In other words, it looks as though it traveled both paths as a wave and interfered with itself. The delayed part comes from the fact that we can decide which method (particle-like detection or wave-like detection) to use after the photon has crossed the first beam splitter. This leads to puzzling questions about how or when the photon decides whether it behaves like a particle or a wave.[12]

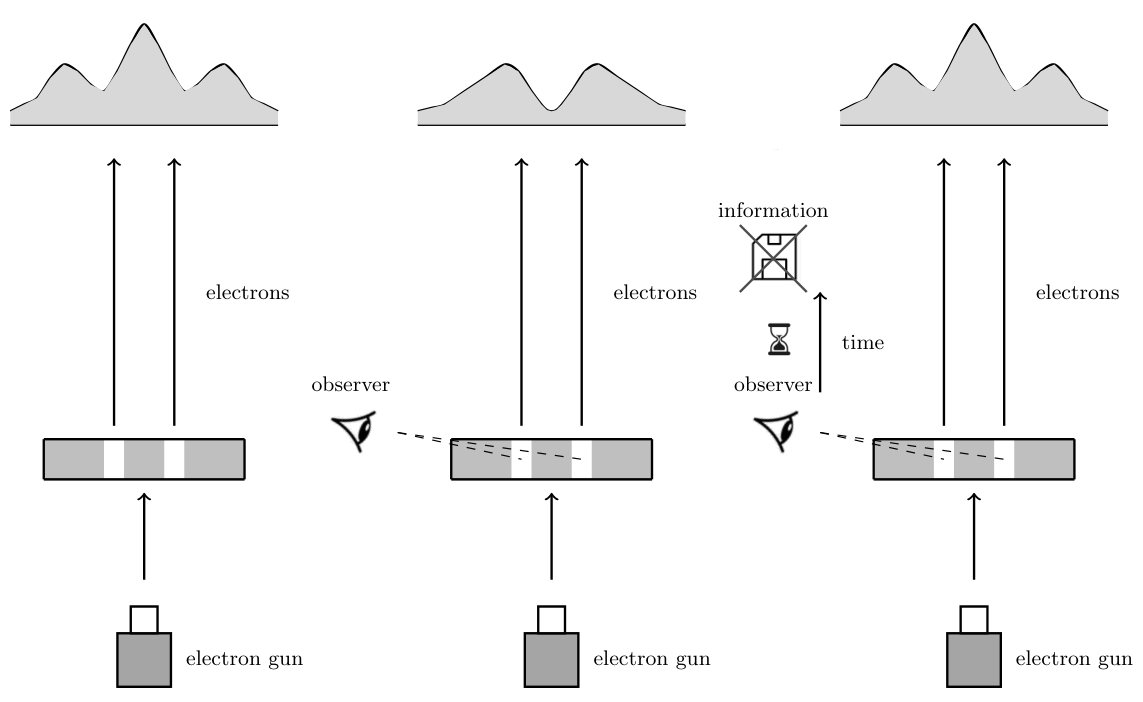

Taking this puzzling idea further, physicists M. Scully and others proposed something called the quantum eraser.[1] The idea behind the quantum eraser is that if you have which-path information (knowledge of which route the photon took), then you will not see an interference pattern. If you erase or destroy that which-path information, the interference can come back. People often represent this scenario as:

- Do nothing → get an interference pattern

- Measure which path → lose the interference

- Erase the which-path information → interference returns

The figure above illustrates what some people want us to believe. However, this interpretation of the experiment is incorrect.

This sounds strange on its own, but it gets even more intriguing when combined with the delayed choice aspect. One version of this experiment, performed by Yoon-Ho Kim and collaborators, entangles each photon that goes through the double-slit or beam splitter with another photon (its entangled partner).[2] By measuring the partner photon in different ways, one might either reveal or hide the which-path information of the original photon. Crucially, some of these partner-photon measurements happen after the first photon has already been detected, making it seem like we can retroactively decide whether the initial photon displayed wave-like or particle-like properties.

The Quantum Eraser Setup and Observations

When people first hear this explanation, they often believe that the “eraser” is literally changing the past or causing some kind of backward-in-time effect. However, the details of the experiment show that what is really happening has more to do with how the entire set of data is sorted rather than any genuine retrocausality.[3] In quantum optics experiments, it is common to use entangled photon pairs to reduce noise. By measuring one photon, you can know when its partner arrives at the detector. This technique is often referred to as “heralded” detection, because the detection of the first photon “heralds” the presence of the second. This approach enables scientists to pick out valid signals from a sea of random noise.

In the Kim et al. version of the delayed choice quantum eraser, you start by generating pairs of entangled photons. One photon (the “signal” photon) travels toward a detecting device through something akin to a double-slit or beam splitter setup, while the other photon (the “idler” or “heralding” photon) travels to a different set of detectors that can either reveal which-path information or erase it.[2] The key is that by looking at the idler photon’s detection in certain ways, one can figure out which path the signal photon took. Alternatively, one can measure the idler in such a way that you can no longer tell which path the signal photon took, thus “erasing” the path information.

A crucial point is what happens when you combine all the detected signal photons without regard to how the idler photons were measured. One might expect, if the which-path information truly had been erased, that you would see a simple interference pattern reminiscent of a traditional double-slit experiment. But that is not what happens. In fact, if you lump all the signal photon detections together, you do not see a familiar bright-and-dark-fringes pattern. Instead, you get a seemingly random distribution. There is no obvious interference in that overall data.

Where does the interference come from, then? It emerges only when you look at specific subsets of the data. For instance, you can take note of which idler detector clicked, and sort the signal photon data accordingly. In some subsets, you may see a pattern that looks like interference, while in another subset, you see a similar pattern that is shifted out of phase. If you add those subsets together, the interference patterns cancel each other out, leaving you with no net interference in the sum. Therefore, it is misleading to say that the experiment recovers a simple double-slit interference pattern just by erasing which-path information. Instead, it recovers something that superficially looks like interference, but which is tightly bound to how you filter or classify the detection events. Here is also another good video regarding the matter “Boy, Was I Wrong! How the Delayed Choice Quantum Eraser Really works”.[6]

The outcome reveals that the “mystery” lies in post-selection and data analysis. Because the experiment uses entangled photons, each signal photon detection can be matched to a particular idler photon detection. Depending on which idler detector saw the photon, you place that detection event into a certain category or subset. Each category displays different properties, like shifting interference patterns or no interference at all. When you interpret these findings without an awareness of how the data is being organized, it might appear as though later choices alter earlier events. But once you see that the interference is tied to carefully chosen data subsets, the illusion of time-traveling information vanishes.[3]

Furthermore, another subtlety in the Kim et al. experiment is that additional optical elements (such as a nonlinear crystal placed behind the slits, which facilitates down-conversion, and prisms that separate the photon paths) already “select” or filter out certain path information by virtue of their design.[2] Phase matching requirements in the crystal mean that only certain photon momenta lead to efficient creation of entangled pairs, effectively shaping the final pattern. On top of that, the supposed “eraser” portion of the apparatus contains two slightly different interferometers set up to produce phase-shifted interference. Hence, the experiment is strongly guided by how these optical elements are arranged, which influences the data we see.

Conclusion

In summary, while the delayed choice quantum eraser experiment is often described as a clear demonstration of retrocausality, most physicists interpret it as a more nuanced illustration of quantum correlations and post-selection. The actual total data-the sum of all detections-shows no simple return of the classical double-slit interference pattern. Instead, the pattern reappears only in specially selected subgroups of the data, where the path information is effectively obscured. This breakdown into subgroups produces patterns that can interfere constructively in one subset and destructively in another, thus canceling out when everything is viewed at once.

Therefore, although the experiment is undoubtedly clever and important for understanding quantum measurement, it does not allow us to change the past or send messages backward in time. Its real lesson is that quantum physics requires careful thinking about what we measure, how we measure it, and how we choose to organize or “tag” our results. The delayed choice quantum eraser reminds us that at the quantum level, reality often defies the simple, intuitive interpretations we might be tempted to adopt, but it does so in ways that remain consistent with standard quantum theory-no time-traveling signals or mystical retrocausality required.

References

- 1.Scully, Marlan O.; Kai Drühl (1982). "Quantum eraser: A proposed photon correlation experiment concerning observation and "delayed choice" in quantum mechanics". Physical Review A. 25 (4): 2208-2213. Bibcode:1982PhRvA..25.2208S. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.25.2208. ↩

- 2.Kim, Y.H., Yu, R., Kulik, S.P., Shih, Y. and Scully, M.O., 2000. Delayed "choice" quantum eraser. Physical Review Letters, 84(1), p.1. ↩

- 3.Kastner, R.E., 2019. The 'delayed choice quantum eraser'neither erases nor delays. Foundations of Physics, 49(7), pp.717-727. ↩

- 4.Hossenfelder, S. (2021). The Delayed Choice Quantum Eraser, Debunked [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RQv5CVELG3U ↩

- 5.Carroll, S. (2019). The Notorious Delayed-Choice Quantum Eraser. Preposterous Universe. https://www.preposterousuniverse.com/blog/2019/09/21/the-notorious-delayed-choice-quantum-eraser/ ↩

- 6.Ash, A. (2022). Boy, Was I Wrong! How the Delayed Choice Quantum Eraser Really works [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s5yON4Gs3D0 ↩

- 7.Wheeler, J.A. (1978). "The 'Past' and the 'Delayed-Choice' Double-Slit Experiment". In A.R. Marlow (ed.), Mathematical Foundations of Quantum Theory. Academic Press. pp. 9-48. ↩

- 8.Wheeler, J.A. (1984). "Quantum Theory and Measurement". In J.A. Wheeler & W.H. Zurek (eds.), Princeton University Press. pp. 182-213. ↩

- 9.Feynman, R.P., Leighton, R.B., & Sands, M. (1965). "The Feynman Lectures on Physics, Vol. III: Quantum Mechanics". Addison-Wesley. Chapter 1. ↩

- 10.Hellmuth, T., Walther, H., Zajonc, A., & Schleich, W. (1987). "Delayed-choice experiments in quantum interference". Physical Review A, 35(6), 2532-2541. ↩

- 11.Jacques, V., Wu, E., Grosshans, F., Treussart, F., Grangier, P., Aspect, A., & Roch, J.F. (2007). "Experimental realization of Wheeler's delayed-choice gedanken experiment". Science, 315(5814), 966-968. ↩

- 12.Ma, X., Kofler, J., & Zeilinger, A. (2016). "Delayed-choice gedanken experiments and their realizations". Reviews of Modern Physics, 88(1), 015005. ↩