String theory represents one of the most ambitious frameworks in theoretical physics, attempting to reconcile quantum mechanics with general relativity and potentially describe all fundamental forces and particles in nature. This theory has undergone significant evolution since its inception, transforming from a model of strong nuclear interactions to a candidate for a unified theory of everything.

Historical Background and Motivation

The development of string theory emerged from the broader context of 20th-century physics, which was marked by two revolutionary but seemingly incompatible frameworks: general relativity and quantum mechanics. General relativity, developed by Albert Einstein, successfully describes gravity and the large-scale structure of spacetime, while quantum mechanics provides an extraordinarily accurate description of phenomena at subatomic scales. Despite their individual successes, these theories fundamentally clash when attempting to describe extreme scenarios like the interiors of black holes or the first moments after the Big Bang. This theoretical inconsistency, particularly the problem of quantum gravity, created the intellectual environment in which string theory would eventually emerge. Physicists were searching for a mathematical framework that could describe all fundamental forces-electromagnetic, weak nuclear, strong nuclear, and gravitational-within a single coherent theory.

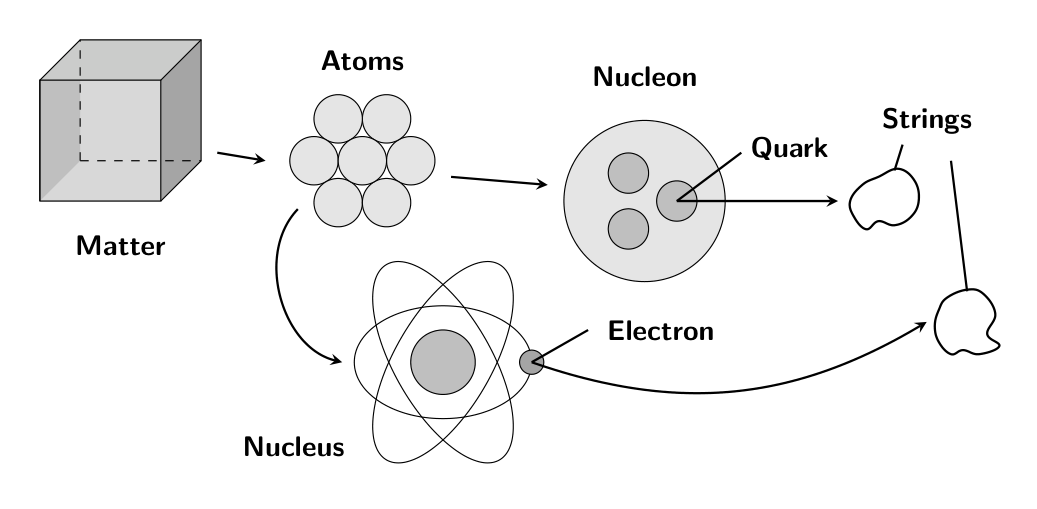

String theory was not initially conceived as a theory of everything or even as a theory of quantum gravity. Rather, it emerged in the late 1960s as an attempt to describe the strong nuclear force that binds protons and neutrons together in atomic nuclei. Before the development of quantum chromodynamics (QCD), physicists were searching for mathematical models to explain the peculiar patterns observed in strongly interacting particles (hadrons). The initial string models proposed that these particles could be represented not as point-like entities but as tiny one-dimensional vibrating strings.[1] In this original conception, different vibrational modes of these strings would correspond to different particles, similar to how different vibrations of a guitar string produce different musical notes. However, this initial application of string theory faced significant challenges and was eventually abandoned in favor of quantum chromodynamics, which provided a more successful description of the strong nuclear force using point-like particles called quarks and gluons.

Transition to a Theory of Quantum Gravity

In a remarkable twist of scientific development, the very features that made string theory unsuitable as a theory of nuclear physics made it an intriguing candidate for a quantum theory of gravity. In the early 1970s, physicists discovered that the string models necessarily included a massless spin-2 particle-exactly what would be expected for the graviton, the hypothetical particle that would carry the gravitational force in a quantum theory of gravity.[2] This discovery shifted the focus of string theory research. Instead of viewing strings as models of hadrons, physicists began exploring strings as fundamental entities underlying all particles and forces in nature. The characteristic length scale of these strings was reconceived to be extremely small-on the order of the Planck length (approximately 10^-35 meters)-explaining why they would appear as point-like particles in all existing experiments. This transition represented a fundamental change in ambition: string theory was no longer just a theory of the strong force but a potential unified theory of all fundamental interactions, including gravity.

The earliest formulation of string theory was bosonic string theory, which described only bosons-particles that transmit forces, such as photons (carriers of electromagnetic force) and the hypothetical graviton (carrier of gravitational force). This version required a 26-dimensional spacetime for mathematical consistency, far beyond our observed four dimensions (three spatial dimensions plus time). While mathematically intriguing, bosonic string theory suffered from significant problems, including the prediction of particles called tachyons (particles that travel faster than light, violating causality) and its inability to describe fermions-the matter particles like electrons and quarks that make up our world.

Superstring Theory

The limitations of bosonic string theory led to the development of superstring theory in the mid-1970s. This more sophisticated version incorporated a theoretical principle called supersymmetry, which proposes a fundamental relationship between bosons and fermions.[3] In superstring theories, every boson has a fermion counterpart, and vice versa. Superstring theory reduced the required number of dimensions from 26 to 10 (nine spatial dimensions plus time) and eliminated the problematic tachyons of the earlier theory. Perhaps most importantly, it could now describe both force-carrying bosons and matter-forming fermions, making it a more viable candidate for a comprehensive physical theory. As research into superstring theory progressed through the 1980s, physicists discovered that there were actually five different consistent versions of the theory:

-

Type I string theory: Includes both open strings (with endpoints) and closed strings (forming loops)

-

Type IIA string theory: Contains only closed strings and features non-chiral (left-right symmetric) N=2 supersymmetry in ten dimensions

-

Type IIB string theory: Also contains only closed strings but with a different symmetry structure than Type IIA

-

Heterotic SO(32) string theory: Contains only closed strings with left-moving bosonic modes and right-moving superstring modes, has gauge group SO(32), and possesses chiral N=1 supersymmetry in ten dimensions

-

Heterotic E8×E8 string theory: Similar to Heterotic SO(32), contains only closed strings, combines left-moving bosonic modes with right-moving superstring modes, but features the gauge symmetry E8×E8. It also exhibits chiral N=1 supersymmetry in ten dimensions

Each version has different types of strings and predicts particles with different symmetry properties. This multiplicity of theories initially seemed problematic-if string theory was supposed to be a unique “theory of everything,” why were there five different versions?

The Role of Extra Dimensions

One of the most counterintuitive aspects of string theory is its requirement for extra spatial dimensions beyond the three we experience in everyday life.[4] In superstring theory, spacetime must be 10-dimensional for the mathematics to remain consistent (11-dimensional in the case of M-theory, which we’ll discuss shortly). To reconcile this with our observed four-dimensional spacetime, string theorists propose that the extra dimensions are “compactified”-curled up into extremely small spaces that are impossible to detect with current technology. To visualize this, imagine an ant walking on a garden hose. From far away, the hose appears to be one-dimensional (its length), but up close, the ant experiences two dimensions (length and circumference).

These extra dimensions aren’t arbitrary-their precise geometric configuration, often modeled as complex shapes called Calabi-Yau manifolds, would determine the properties of the particles and forces we observe in our four-dimensional world.[5] Different configurations of these hidden dimensions could, in principle, lead to different physical laws. Another approach to dealing with extra dimensions is the “brane-world scenario,” where our observable universe is conceptualized as a four-dimensional subspace (or “brane”) embedded within a higher-dimensional space. In this picture, most particles and forces are confined to our four-dimensional brane, while gravity can propagate through the full higher-dimensional space, potentially explaining why gravity appears so much weaker than the other fundamental forces.

The primary motivation for string theory has been to resolve the incompatibility between quantum mechanics and general relativity. This incompatibility becomes apparent when attempting to apply quantum principles to gravity in the same way they’ve been successfully applied to other forces. When physicists try to formulate a quantum field theory of gravity using point particles, they encounter unresolvable infinities in their calculations. String theory potentially resolves this problem by replacing point particles with extended objects (strings), which “smear out” the interactions and eliminate the problematic infinities.[6]

In string theory, gravity emerges naturally as one vibrational mode of the fundamental strings corresponds to a massless, spin-2 particle-precisely the properties expected for the graviton. This means that string theory automatically includes gravity, rather than having to add it as a separate force. Furthermore, by incorporating general relativity’s curved spacetime concept and quantum mechanics’ probabilistic framework, string theory attempts to provide a consistent mathematical language for describing all physical phenomena, from subatomic particles to black holes and the cosmos at large.

M-Theory and Dualities

In the mid-1990s, theoretical physicist Edward Witten proposed that the five seemingly different string theories were actually connected as different manifestations of a single underlying theory, which he called “M-theory”.[7] This 11-dimensional theory isn’t fully formulated mathematically, but it represents a higher-level framework that encompasses all string theories. The “M” in M-theory has been interpreted variously as standing for “membrane,” “matrix,” “mystery,” or “mother”-reflecting both the theory’s incorporation of higher-dimensional objects called branes (generalizations of strings to two or more dimensions) and the incomplete nature of our understanding of the full theory.

The connections between different string theories are established through relationships called “dualities”-mathematical transformations that show how apparently different physical descriptions can represent the same underlying physics. Two particularly important types of dualities in string theory are:

-

S-duality: Relates a strongly interacting theory to a weakly interacting one. For example, Type I string theory is equivalent under S-duality to the SO(32) heterotic string theory. This duality is powerful because it allows physicists to study strong interactions (which are mathematically difficult) by transforming the problem into weak interactions (which are more tractable).

-

T-duality: Relates strings moving in a space with a compact dimension of radius R to strings moving in a space with radius 1/R.[8] This counterintuitive duality suggests that physics at very small distance scales is equivalent to physics at very large scales in a dual description.

These dualities revealed that what initially appeared to be five distinct theories were actually different perspectives on the same underlying physical reality, similar to how a single object might cast different shadows depending on the angle of illumination.

Current Status and Challenges

Despite its mathematical elegance and the hope it offers for unification, string theory faces significant challenges that have led to ongoing debates about its status in the physics community. String theory doesn’t yet have a complete, non-perturbative formulation. The theory is primarily defined through approximation techniques (perturbation theory), which work well for certain calculations but don’t provide a full definition of the theory in all circumstances. This limitation has hampered progress in understanding some of the theory’s most fundamental aspects.

String theory appears to allow for an enormous number of possible vacuum states-different configurations of the compact dimensions that would lead to different physical laws. This vast “landscape” of possibilities (estimated to be around 10^500 different possible universes) has raised questions about the theory’s predictive power. If string theory allows for so many possibilities, how can it make definitive predictions about our specific universe?[9]

Perhaps the most significant challenge facing string theory is the lack of direct experimental evidence. The characteristic energy scale at which stringy effects would become apparent is the Planck scale, far beyond the reach of current or foreseeable particle accelerators. This has led critics to question whether string theory should be considered a physical theory or a mathematical framework that may not describe our actual universe.

Despite these challenges, research in string theory continues along several fronts: Developing more sophisticated mathematical tools to better understand the theory. Exploring connections between string theory and observable phenomena like cosmology or condensed matter physics. Investigating the AdS/CFT correspondence, a relationship discovered in 1997 that connects string theory to certain quantum field theories and has applications beyond string theory itself.[10] Searching for potential experimental signatures that might be detectable at lower energies.

Conclusion

String theory represents one of the most ambitious intellectual endeavors in theoretical physics-an attempt to formulate a single mathematical framework that could explain all physical phenomena from the subatomic to the cosmic scale. From its humble origins as a model of the strong nuclear force to its development into a candidate for a “theory of everything,” string theory has undergone remarkable evolution.

The theory has stimulated important advances in mathematics and theoretical physics, providing new insights into black holes, cosmology, and quantum gravity. Yet it remains a work in progress, facing significant theoretical challenges and lacking experimental confirmation.

The history of string theory illustrates both the power and limitations of mathematical beauty as a guide to physical reality. Whether string theory ultimately proves to be the correct description of nature or simply a stepping stone toward a different unified theory, its development has already enriched our understanding of the fundamental questions that lie at the intersection of quantum mechanics and gravity.

References

- 1.Veneziano, G., 1968. Construction of a crossing-symmetric, Regge-behaved amplitude for linearly rising trajectories. Il Nuovo Cimento A, 57(1), pp.190-197. ↩

- 2.Scherk, J. and Schwarz, J.H., 1974. Dual models for non-hadrons. Nuclear Physics B, 81(1), pp.118-144. ↩

- 3.Wess, J. and Zumino, B., 1974. Supergauge transformations in four dimensions. Nuclear Physics B, 70(1), pp.39-50. ↩

- 4.Green, M.B., Schwarz, J.H. and Witten, E., 1988. Superstring theory: volume 2, Loop amplitudes, anomalies and phenomenology. Cambridge university press. ↩

- 5.Candelas, P., Horowitz, G.T., Strominger, A. and Witten, E., 1985. Vacuum configurations for superstrings. Nuclear Physics B, 258, pp.46-74. ↩

- 6.Green, M.B., Schwarz, J.H. and Witten, E., 1987. Superstring theory: volume 1, Introduction. Cambridge university press. ↩

- 7.Witten, E., 1995. String theory dynamics in various dimensions. Nuclear Physics B, 443(1-2), pp.85-126. ↩

- 8.Polchinski, J., 1998. String theory: Volume 2, superstring theory and beyond. Cambridge university press. ↩

- 9.Susskind, L., 2003. The anthropic landscape of string theory. arXiv preprint hep-th/0302219. ↩

- 10.Maldacena, J., 1999. The large-N limit of superconformal field theories and supergravity. International journal of theoretical physics, 38(4), pp.1113-1133. ↩