Twistor theory, conceived by Sir Roger Penrose in the 1960s, represents a radical reimagining of the mathematical foundations of physics. By encoding the geometry of space-time into complex projective spaces known as twistor spaces, this framework challenges conventional notions of locality and offers novel insights into quantum gravity, particle physics, and the unification of fundamental forces.[4] While rooted in abstract geometry, twistor theory has catalyzed advancements in scattering amplitude calculations, integrable systems, and string theory, bridging pure mathematics with theoretical physics.[2] This report synthesizes its core principles, historical evolution, and implications, emphasizing intuitive explanations over mathematical formalism to make its profound ideas accessible to a broad audience.

Historical Context

Twistor theory emerged during a period of significant theoretical development in general relativity and quantum mechanics, as physicists sought a deeper understanding of Einstein’s equations and a framework capable of reconciling gravity with quantum theory. During the 1950s and 1960s, Roger Penrose, influenced by the geometric foundations of relativity and the non-intuitive behavior of quantum systems, proposed an alternative mathematical structure in which spacetime itself could be understood as an emergent property rather than a fundamental entity.[3] His approach was rooted in the study of spinors-algebraic objects that describe intrinsic angular momentum-and Ivor Robinson’s Robinson congruences, geometric constructs that characterize families of twisting light rays.[2] The central insight of twistor theory was to replace conventional spacetime coordinates with twistors, which naturally encode both position and momentum within a unified complex framework. This reformulation paralleled the quantum mechanical principle of complementarity, wherein physical entities exhibit both wave-like and particle-like properties depending on how they are measured. By shifting the focus from local spacetime descriptions to a more abstract geometric space, Penrose aimed to uncover underlying structures that might offer new perspectives on quantum gravity.

Although twistor theory gained traction in the 1970s as a novel approach to fundamental physics, its non-local formulation initially presented challenges for direct physical applications. However, subsequent developments, particularly in the study of scattering amplitudes and supersymmetric theories, demonstrated its utility in simplifying calculations and revealing hidden symmetries in quantum field theory.

Twistor Space

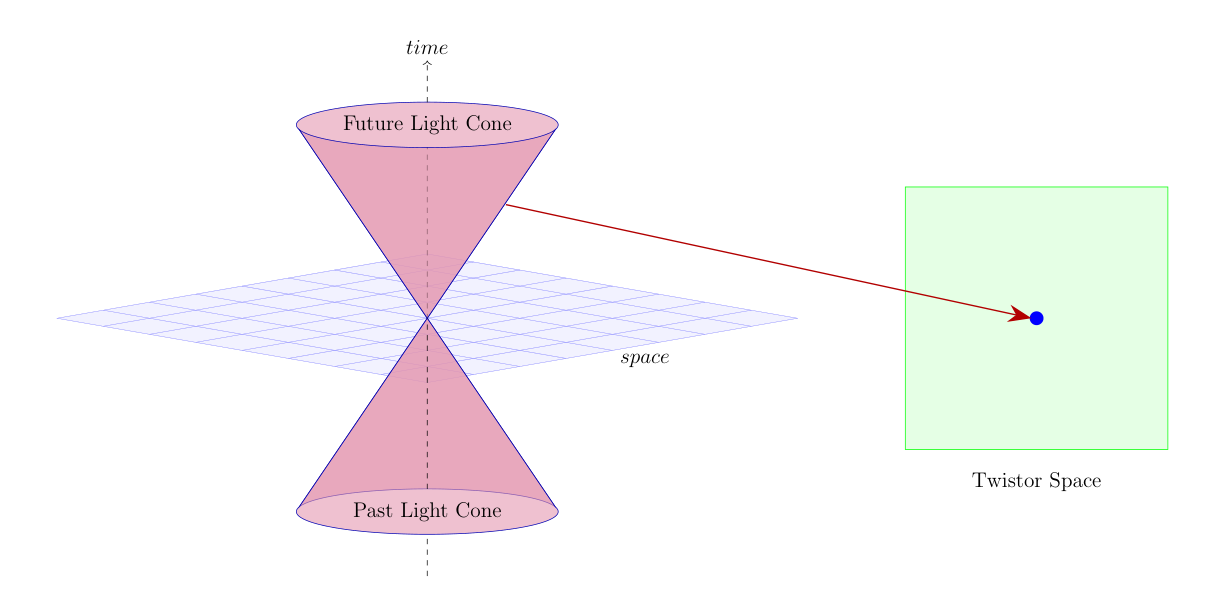

Twistor theory presents a reformulation of spacetime as an emergent construct derived from a more fundamental geometric framework known as twistor space. In this approach, physical events are not inherently defined by traditional coordinate systems but instead correspond to geometric structures within a higher-dimensional complex manifold.[1] A direct analogy is a hologram, in which a two-dimensional surface encodes three-dimensional information through patterns of light interference. Similarly, twistor space-a three-dimensional complex space-encodes four-dimensional spacetime events as algebraic and geometric data. Each point in spacetime is associated with a line in twistor space, while a single twistor represents a massless particle or a light ray propagating through spacetime.[2] This formalism allows for a geometric interpretation of physical phenomena, facilitating computations in quantum field theory and relativity by translating dynamical equations into holomorphic structures. For instance, a photon moving through spacetime can be represented as a helical trajectory in twistor space, encapsulating its direction, energy, and polarization. This encoding offers a significant simplification of the equations governing massless particles, replacing conventional coordinate-based formulations with geometric representations that make the underlying symmetries more explicit.

As we can see in the illustration, each point in twistor space can be associated with a light ray in Minkowski spacetime or more precisely, a family of closely related null directions.

A central aspect of this framework is its reliance on conformal invariance, which prioritizes the preservation of angles rather than absolute distances. This property aligns with the conformal symmetry group of spacetime, which includes transformations such as rotations, translations, and scalings.[3] Since twistor theory emphasizes angular relationships, it provides a natural setting for the study of light-like structures, including the trajectories of massless fields such as photons and gravitational waves. In this context, physical interactions can be understood in terms of their geometric relationships rather than absolute measurements, reflecting the scale-invariant nature of quantum field theory. An intuitive analogy is that of a spiderweb, in which the structural integrity is defined by the angles between its threads rather than their specific lengths. Similarly, twistor theory describes physical processes through the relational geometry of events, offering a reformulation of fundamental interactions that is particularly well suited for studying radiation, scattering amplitudes, and the foundational principles of quantum gravity.

Bridging Geometry and Physics

The Penrose transform, a cornerstone of twistor theory, converts analytic functions on twistor space into solutions of field equations in spacetime, allowing holomorphic functions in twistor space to generate self-dual electromagnetic or gravitational fields.[4] This mechanism generalizes Fourier transforms, operating in a geometric realm tailored to relativistic physics. A major development in this area is Penrose’s nonlinear graviton construction, which demonstrates how deformations of twistor space correspond to self-dual gravitational fields-solutions to Einstein’s equations where spacetime curvature aligns with its own structure.[3] This can be visualized as a rubber sheet (representing twistor space) deforming under stress, with the induced curvature mirroring gravitational effects in spacetime. Although initially limited to self-dual cases, this insight paved the way for understanding gravity within twistor geometry.

To extend these ideas beyond self-dual fields, physicists introduced ambitwistors, capturing both incoming and outgoing radiation, effectively bundling light rays into complex structures that unify a particle’s past and future trajectories. This ambitwistor framework forms the foundation of modern twistor string theories, linking twistor geometry directly to the scattering amplitudes of particles.[6] Twistor methods have dramatically simplified calculations in quantum chromodynamics (QCD) and other gauge theories, replacing the exponentially complex computations of traditional Feynman diagrams with geometric integrals over twistor space. For instance, the RSV formula, derived from twistor string theory, allows the computation of particle interaction probabilities through holomorphic maps, transforming lengthy algebraic calculations into elegant geometric constructions.[1] These innovations reveal a deep connection between geometry and fundamental physics, not only streamlining scattering amplitude computations but also suggesting new pathways toward unifying quantum field theory and gravity.

Twistor String Theory

Twistor string theory represents a synthesis of Penrose’s twistor geometry and string theory, offering novel approaches to longstanding challenges in quantum field theory and quantum gravity. By encoding spacetime events into complex projective spaces, this framework transforms intractable calculations in particle physics into geometric problems, revealing hidden structures in scattering amplitudes and gravitational interactions.[6] Emerging from early 21st-century attempts to simplify Yang-Mills theory computations, twistor string theory has evolved into a tool for exploring holography, supersymmetry, and the amplituhedron-a geometric object replacing traditional Feynman diagrams. Conventional string theories, which describe particles as vibrating strings in 10-dimensional spacetime, faced challenges in connecting directly to 4-dimensional quantum field theories like the Standard Model.

A breakthrough came when Edward Witten proposed redefining string dynamics not in physical spacetime but in twistor space-a complex geometric framework where spacetime points are represented as lines or curves.[6] This shift aimed to simplify the computation of scattering amplitudes, the probabilities governing particle collisions, which were notoriously laborious using Feynman diagrams. The motivation behind this approach was twofold: first, to unify quantum field theory and gravity by embedding string theory into twistor space, and second, to increase computational efficiency by leveraging the holomorphic properties of twistor geometry. These properties allow for a transformation of complex algebraic calculations into more intuitive geometric relations, much like how projecting a 3D object onto a 2D plane simplifies its description. Twistor space encodes both the position and momentum of a particle into a single complex object, extending this principle by treating strings as holomorphic curves-surfaces defined by complex equations in twistor space. These curves generalize the worldsheets of conventional string theory, replacing their real-number parametrization with complex coordinates.

One of the key insights from twistor string theory is how it revolutionizes the understanding of scattering amplitudes. In this framework, particles correspond to points or lines in twistor space, and their interactions are encoded in the geometry of intersecting curves. The introduction of the amplituhedron, proposed by Arkani-Hamed and Trnka, builds upon this approach by replacing traditional Feynman diagrams with a geometric volume in Grassmannian space, allowing scattering amplitudes to be computed as the volume of this shape rather than through direct spacetime interactions.[1] This geometric intuition streamlines quantum predictions, akin to calculating the area of a polygon rather than counting individual tiles. A particularly important advancement enabled by twistor string theory is the development of the Maximal Helicity Violating (MHV) formalism, which provides compact formulas for gluon scattering amplitudes in Yang-Mills theory. Traditionally, these calculations required summing thousands of Feynman diagrams, but twistor-based methods reduce the complexity significantly by representing interactions as integrals over geometric configurations in twistor space. The Britto-Cachazo-Feng-Witten (BCFW) recursion technique further enhances this efficiency by breaking down complex amplitudes into simpler ones, constructing intricate scattering processes piece by piece. As a result, calculations that once required supercomputers can now be derived using elegant hand-calculated formulas, underscoring the predictive power of twistor string theory in high-energy physics.

Despite its successes, twistor string theory initially faced criticism for predicting conformal (scale-invariant) gravity, a theory that does not match observed physics. However, refinements demonstrated that specific configurations can reproduce Einstein gravity when combined with cosmological constants, suggesting a deeper connection to holography, where gravitational effects in four-dimensional spacetime emerge from data encoded on a three-dimensional boundary. Recent research has extended this concept by exploring minimal-tension strings in anti-de Sitter (AdS) spacetimes, where bulk gravitational phenomena manifest through twistor correlations at the boundary-an idea reminiscent of a hologram, where a three-dimensional image is reconstructed from two-dimensional data. This framework naturally accommodates supersymmetry, allowing particles and their superpartners to emerge from different vibrational modes of the same twistor string. In supersymmetric twistor space, graded coordinates represent superpartners, simplifying calculations in super-Yang-Mills and supergravity theories. Notably, the maximally supersymmetric Yang-Mills theory (N=4 SYM) becomes more tractable in twistor space, with its scattering amplitudes aligning with those derived from conventional string theory in higher-dimensional spacetimes. Twistor string theory thus not only provides a new mathematical perspective on particle interactions but also deepens the understanding of quantum gravity, hinting at an underlying geometric unity between fundamental forces.

Challenges and Prospects

A persistent challenge in twistor theory, known as the googly problem, arises from its traditional emphasis on left-handed (self-dual) fields, which initially left right-handed (anti-self-dual) fields without a clear formulation within the framework. Named after the deceptive spin of a cricket ball’s “googly” delivery, this issue required a reevaluation of twistor geometry to accommodate both helicities symmetrically. In response, Penrose introduced palatial twistor theory, which extends twistor space into a noncommutative geometric setting where spacetime points acquire quantum-like fuzziness. Although still speculative, this approach seeks to unify left- and right-handed fields within a single formalism, potentially resolving the longstanding asymmetry in twistor-based descriptions of fundamental interactions.

More broadly, twistor theory challenges the conventional understanding of spacetime as a fundamental entity, instead proposing that it emerges from a deeper geometric structure, much as macroscopic thermodynamic properties such as temperature arise from microscopic molecular motion. This perspective resonates with modern quantum gravity approaches, where spacetime is treated as a derived construct rather than a fixed background. For instance, loop quantum gravity envisions spacetime as a discrete network of quantum states, while twistor theory provides an alternative, continuum-based description grounded in complex geometry.[2] Beyond its implications for physics, twistor theory has made significant contributions to mathematics, influencing the study of integrable systems, where solitons and other nonlinear wave solutions admit twistor-based descriptions; representation theory, where twistor symmetries provide deeper insights into Lie groups and algebras; and differential geometry, where twistor methods have resolved problems in four-dimensional topology.

Despite these advances, twistor theory remains an evolving framework with unresolved challenges, including the incorporation of matter fields and the full nonlinear structure of general relativity. However, ongoing research in supersymmetric generalizations (supertwistors), holographic dualities, and modern mathematical structures such as the positive Grassmannian continues to expand its relevance, particularly in refining scattering amplitude calculations and exploring the geometric foundations of quantum field theory.[1]

Conclusion

Twistor theory exemplifies the power of geometric thinking in physics. By transcending coordinates and embracing complex manifolds, it provides a unified language for relativity, quantum theory, and beyond. While its ultimate goal-a complete theory of quantum gravity-remains elusive, twistor methods have already reshaped scattering amplitude computations, illuminated integrable systems, and inspired string theory innovations. As Penrose’s vision evolves, twistor theory stands as a testament to the fertile interplay between abstract mathematics and the quest to decode the universe’s deepest laws.

References

- 1.Adamo, T., 2017. Lectures on twistor theory. arXiv preprint arXiv:1712.02196. ↩

- 2.Huggett, S.A. and Tod, K.P., 1994. An introduction to twistor theory (No. 4). Cambridge University Press. ↩

- 3.Penrose, R. and MacCallum, M.A., 1973. Twistor theory: an approach to the quantisation of fields and space-time. Physics Reports, 6(4), pp.241-315. ↩

- 4.Penrose, R., 1987. On the origins of twistor theory. Gravitation and geometry, pp.341-361. ↩

- 5.Mogi, Ken. (2000). Response Selectivity, Neuron Doctrine, and Mach’s Principle in Perception. 10.1007/978-0-585-29605-0_14. ↩

- 6.Witten, E., 2004. Perturbative gauge theory as a string theory in twistor space. Communications in Mathematical Physics, 252, pp.189-258. ↩